Re-weaving community: Across the generations, everyone contributing to a good life

The heart of Wesley Rātā Village is its incredible community – the residents, Village Guiding Group, Te Āti Awa, Hutt City Council, and the many supportive locals and businesses. More than just a place; it’s a living, breathing intergenerational community, where connections are nurtured and well-being is most important. Watch this inspiring video celebrating community innovation, of doing things together in a new way!

Connecting Hearts: The Revitalisation of Coppard Reserve in Leithfield Village

Uniting for a Shared Vision

The journey towards the revitalisation of Coppard Reserve began when the Leithfield Community Centre, initially established to oversee the community hall, evolved into a platform for residents to share ideas and aspirations. Jo Hassall, a driving force behind the community centre, recognised the importance of encouraging locals’ involvement and keeping them well-informed. With each meeting and mailbox run, more residents joined the conversation, and the email list grew to around 70 people.

Early discussions about the park revolved around creating history boards to showcase the heritage of the reserve. The original spark for this idea was from a local primary school pupil, and locals curated the story and graphics for the history boards. Though it took three years to bring the idea to fruition, these efforts sparked a renewed sense of community connection and engagement in the reserve.

From Small Wins to Big Dreams

During these early endeavours, Jo began to envision a more extensive revitalisation of the reserve. Seeking input from the community through mail drops, she received valuable suggestions, including a request for a basketball court and cross trainers that both teenagers and older adults could use. The project required amending the reserve’s management plan, a potentially daunting process, but with Vanessa’s assistance, the public consultation and feedback collection proved successful.

The Power of Community Engagement

Vanessa emphasised that the key to this progress was ensuring that the community were listened to during the consultation period, and that their final submission was well represented.

“We did get stalled a little bit along the way, with our local government operating in a post-covid recovery space it. It was important through the long timeline to stay in touch with the community, keeping them well informed throughout the process.”

Overcoming Challenges and Nurturing Support

It was while progressing through the approval process, that Jo encountered initial scepticism about the availability of grants. Undeterred, she pursued various funding avenues, adopting a “you don’t get if you don’t ask” mindset. This dedication bore fruit when the Rātā Foundation generously funded the entire basketball court and three cross trainers, amounting to $61,500. Jo emphasised that communities should not be deterred by formalities of the application processes and encouraged using plain language.

“It’s important that communities take the first steps towards helping themselves. Councils only have so much money, but if they see your efforts and you ask for guidance through their processes, they are often happy to jump in and help. The process can feel like it takes forever, but this is the time to stick to your guns and rally the community from consultation, through any funding hurdles. Council can give lists of places you can apply to, and also help with funding applications.“

The Transformation and Beyond

With funding secured, the community sprang into action. Volunteers undertook the installation of the basketball hoop and cross trainers, making use of their skills and resources. The removal of hedge to bring in more natural light was huge task undertaken by local residents, in accordance with the Council’s health and safety requirements. The entranceway received a facelift, using soil from the area to create mounds for planting. The transformation of the reserve attracted increased foot traffic, with families and visitors enjoying the new facilities and general ambiance.

Lessons Learned and Sharing the Journey

Jo emphasised the importance of perseverance and patience when collaborating with Councils, as their processes can be time-consuming. She encourages communities to stay the course, maintain open communication, and seek help from the Council when needed. By sharing her experiences and resources with other community groups, Jo supported them to learn by doing, to navigate the application processes and secure funding for their own projects.

A Bright Future and Ongoing Collaboration

Coppard Reserve’s revitalisation journey continues with evolving ideas, such as the potential inclusion of a herb garden, while preserving ample green space. The community’s enthusiasm and dedication has created a vibrant and well-utilised hub, fostering a sense of ownership and connection among residents.

The story of Coppard Reserve’s revitalisation serves as a testament to the power of community-led development, of perseverance, and collaboration. By nurturing a shared vision, seeking support, building connections and using the assets that already exist in their place, Leithfield Village has created a space that reflects its unique heritage and meets the diverse needs of its residents. As other communities embark on their own revitalisation projects, the lessons learned from this journey provide valuable insights and inspiration.

How Communities Awaken

These essays delve into key community conversations from both the personal and communal perspective. The chapters break down the necessary ingredients for Active Citizenship, framing an understanding of our world where we as citizens can identify the tools, resources and inner drive to make the change we want to see.

Have a look at this diagram that helps us to visualise how these conversations sit together.

vivian’s essays were core resources in the Taranaki Active Citizenship masterclass process. Below you will find our conversations around each chapter and some accompanying videos from Tu Tama Wahine. Read our story, Fostering Active Citizenship – Learning from Taranaki to find out more.

Diving deeper – reflections from a community-led lens

Community

If you spend a little time observing birds in our landscape, you will undoubtedly notice the complexity and beauty of the feather. Pick up a discarded duck feather at the local gardens, you’ll note its fragility, those fluffy little soft baby hairs, but also those iridescent, waterproof ones that automatically smooth together to form a strong barrier against the elements.

“Mā te huruhuru ka rere te manu – without feathers, the bird cannot fly.”

vivian draws from a lifetime in community – from activism, social entrepreneurship, disruption, and service, to identify the core elements of conversation in our communities. Looking at the speed of change across our social and economic lives, community is identified as messy and contradictory, complex, growing, living, active and unique to place. This conversation challenges us to consider what we have to offer, where we come from and where opportunity lies.

Tess Trotter, IC Communications.

Citizenship

“Citizenship is that part of ourselves that we step into when we choose to serve the things that are beyond ourselves”.

Community-led development (CLD) reclaims the idea of active citizenship as a whole spectrum of community activity that includes those leading out front, through to the smallest steps we might take in our own household, neighbourhood or wider whānau to make our lives and the world a better place.

Citizenship matters and requires our urgent attention. In this chapter, vivian reminds us of the work we need to do to collectively rebuild and nurture our shared sense of belonging, contribution, committed action as citizens. At the heart of both citizenship and CLD is relationship, with conversations the key first step. But not just any conversations. Honest, open and intentional conversations that welcome diverse perspectives and challenge us to unpack what really holds us back – injustice, colonisation, racism, consumerism to name but a few. It’s the work we must do on our own and together. Time to get started!

Megan Courtney, IC

Invitation

“How valuable do you expect this experience to be?“

The message about ‘getting the invitation right’ really struck me as central to CLD practice. We invite people to be active citizens, engaging everyone’s strengths, growing shared local visions. The invitation feels like a potluck dinner compared to being a consumer at a café: everyone brings their gifts, there’s curiosity about what feast we might create collectively, relationships grow and often stretch us into shaping bold visions and bringing them into reality

Margy-Jean Malcolm IC

Stretching the Invitation Conversation

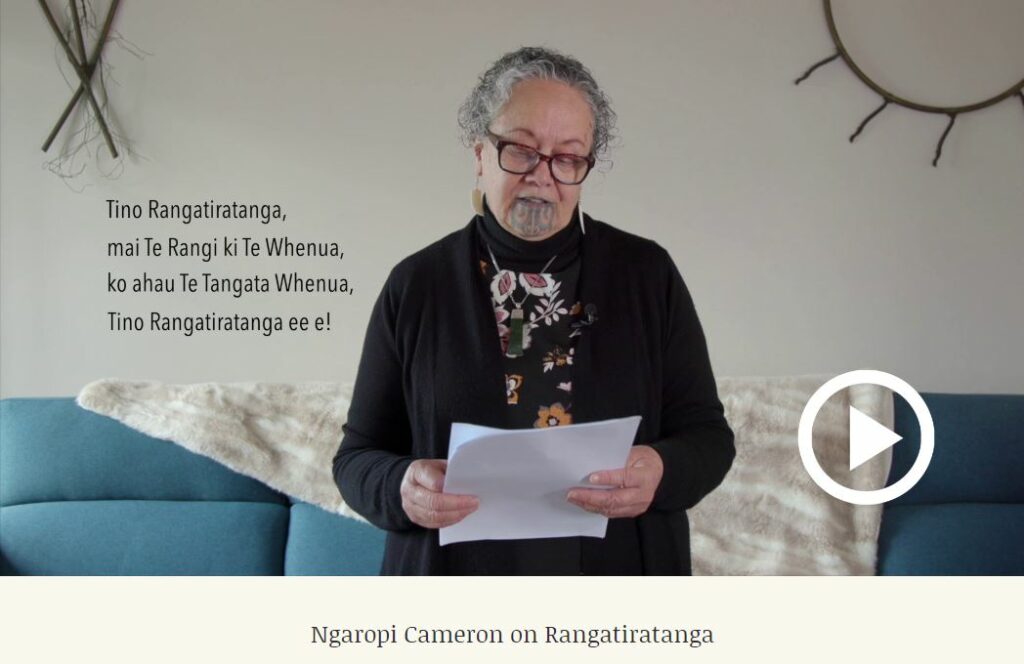

Presented by Ngaropi Cameron, Director, Tū Tama Wāhine o Taranaki

Possibility

“The fact of this is often taken for granted: human beings are community-making creatures.“

I loved the insight in this chapter about cultivating an imaginative mind to stretch our sense of what is possible. A CLD mindset focuses on strengths, assets, possibilities as the lifeblood from which healing and transformation happen. Fun, playful, creative dimensions of community-building are so important in lifting us beyond the weight of problems, despair or powerlessness. Together we find our courage to imagine a better future, our confidence to be creative, innovate, and learn by experimenting.

Margy-Jean Malcolm, IC

Ngaropi Cameron on Māramatanga

Ngaropi Cameron, Director, Tū Tama Wāhine o Taranaki

Ownership

“WE’VE GOT SOME challenging things to talk about. And it’s not all going to be positivity and possibility.“

The ownership conversation signals some challenging issues in CLD – it’s not all positivity and possibility. Power, privilege, inter-generational trauma, consumerism and colonisation are both external forces and internal narratives that we need to decolonise to support our sense of agency to make change. It’s an important nudge to notice when we lapse into “them and us” thinking, blame, excuses, denial – and a challenge to take responsibility to “cross the line”, and own our part in co-creating the futures we want.

Margy-Jean Malcolm, IC

Ngaropi Cameron on Rangatiratanga

Ngaropi Cameron, Director, Tū Tama Wāhine o Taranaki

Ownership

The Transformation Of Belonging

“For me, the Ownership Conversation has been a life-long dialogue that has challenged and transformed my understanding of the nature of belonging.“

What’s our relationship with place, land, property? What if ownership was not about possession, but rather a deep sense of belonging and responsibility as ongoing stewards of the places we are connected to? I enjoyed the rich stories of kaitiakitanga of people, planet and place in action in this chapter, which remind us that CLD is about being strong kaitiaki of the past, present and future potential of our communities as places to live, work and play.

Margy-Jean Malcolm, IC

Dissent

“The plain fact of it is this: harmony can not happen if we are all singing the same note.“

From Inspiring Communities work in community-led change, we know that that innovation frequently happens on the edge. Some of the best solutions are created when people sit in relationship and discomfort long enough to really understand each other, and in doing so, uncover new pathways forward.

In CLD, conflict is actually part of good process, not something to be avoided. It’s just what happens when you bring diverse voices, sectors and parts of a community together.

In this chapter vivian reminds us about the need to welcome, hold and work with everyone’s voice – especially those of local citizens. Doing this effectively requires a commitment to host and work through courageous conversations where we all listen and learn to hold multiple truths – the binary of right and wrong does us no favours.

Megan Courtney, IC

Commitment

“THE COMMITMENT CONVERSATION is about the promises you are making to yourself, and to your community.“

In my experience, relational accountability is far more powerful than anything written in a contract. It’s about doing the things we say we’ll do, not wanting to let others down. It’s these trust based relationships that also hold us when our work in community gets tough. We need people around us to tell it like it is, to keep us honest, so that collectively we can speak truth to power and challenge the policy, process and system injustices that often keep the status quo in place. And we need to keep others honest too – words without visible action to follow, is rhetoric at its best.

Megan Courtney, IC

Gifts

“The plain fact of it is this: harmony can not happen if we are all singing the same note.“

These gifts conversation resources stretched my thinking about koha – as a tangible form of reciprocity, trust, whakapapa, connection, relationship – so much more than money. This challenges us to think expansively about what we are each giving and receiving in our community relationships – to grow a shared kete of knowledge, skills, experience, time and resources, yet including money too. CLD calls for deepest respect for the giving and receiving of everyone’s gifts, and in turn activates dignity, mana, wellbeing when we see what together we can make possible.

Margy-Jean Malcolm, IC

Ngaropi Cameron on Koha

Ngaropi Cameron, Director, Tū Tama Wāhine o Taranaki

Action

“The smallest unit of wellbeing for human beings is not found in ourselves as individuals, or even as extended families…..but as communities.“

The CLD Theory of Change that has evolved in Aotearoa is based on the premise that all communities have the potential to thrive. The starting point for change is conversations between people, finding out about what you care about that’s in common and then taking that first next step of doing something small together. From small seeds, bigger things grow.

In this final chapter, vivian reflects on the essential elements for action – starting from where you are, working with what you’ve got and working in ways that are generative and generous. Community is what happens when all our contributions and actions come together, it’s always in movement and needs to be nurtured – not taken for granted.

Megan Courtney, IC

Fostering Active Citizenship — Learning from Taranaki

The individual awakening of citizenship is a critical element in how our communities

develop – because this awakening involves figuring out just what part of making

things better has got your name on it.

vivian Hutchinson 2012

Active Citizenship is term we’re hearing more about and it’s a key foundation of effective community-led development. How Communities Awaken – Tū Tangata Whenua is an award winning four-month Masterclass for active citizenship first established in Taranaki in 2011 now operating as a partnership between Community Taranaki and Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki. Around 350 people have now participated in the Masterclass process, which has evolved a learning approach based on tikanga Māori, wānanga and community-led adult education practices. As a result, a diverse range of community members have now embraced their citizenship, developed a shared language, and formed strong networks across their community.

Masterclass participants deep in conversation.

Photo credit: Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki

But what is Active Citizenship? For Masterclass co-founder, vivian Hutchinson, it’s “about finding purpose, place, relationships, and personal meaning through asking big questions and engaging in deep conversation with others.”

The Taranaki Active Citizenship Masterclass process has come about through skilful curation and longstanding, trusting relationships between vivian and the whanau behind Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki. Awhina Cameron, CEO of Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki, highlights the significance of friendship as the foundation for the collaboration. “Like any small community you can have MOU’s and service level agreements, but the reality of how it works is through friendship and whakapapa. Our work with vivian is an example of this. He was mentored by some of our late, great aunties.”

“The Masterclass really made me stop and re-analyse all my work, particularly the place of social services versus real community engagement.”

“I will now approach my group work much slower. I won’t rush in and fix the problem, instead I will try to think outside the square and use a more inclusive approach.”

Feedback from Masterclass Participants

Photo credit: Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki

Masterclass fundamentals

The concept of invitation and intentional participation is core to the Masterclass approach. vivian notes “the personal invitation to participate helps to curate a diverse network.” People come and choose to become part of the process due to this invitation. Unlike many traditional learning opportunities, individuals are invited to attend as themselves, not as a representative of an organisation or other entity. Awhina adds that this invitation crosses boundaries between work and citizenship – and for many it is an awakening of new ways of thinking.

The Masterclass is a process of conversations. Participants are encouraged to listen and delve deep, listening to stories, considering key questions, and sharing in large and small group circle-based conversations.

Every class is different. I expect to learn as much as I have to share.

vivian Hutchinson

The Masterclass topics of Invitation, Possibility, Ownership, Dissent, Commitment, and Gifts were first offered by the US author Peter Block in his book “Community – the Structure of Belonging” (2008). To this, the Taranaki team added conversations on Community, Citizenship and Action. Workshops on these concepts are held fortnightly, with participants gifted books and a wide range of other readings and resources to explore between. During each workshop, participants lead workshop content by sharing their own history and stories as an introduction to the conversation. Local elders and thought leaders are invited into the conversations to ‘stretch’ them by sharing their perspectives. In terms of Mātauranga Māori, these ‘stretches’ have included insights into Tū Tangata Whenua, Tikanga, Rangatiratanga, Whanaungatanga, Māramatanga, Ōhākī and Koha. (These links will lead you to Te Aka – Māori Dictionary meanings for these words.)

Ngaropi Raumati, Kuia and Director of Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki has created Te Kai a Te Rangatira (2020) This video series is based on her stretch conversations on the topics above.

For many, it’s a challenging process. It invites a slowing down, actively listening and committing to a journey. Awhina notes that the Masterclass is not therapeutic, nor is it mentoring. It allows time and space for people to do some deep thinking about self and place in community, alongside and in conversation with others.

The Masterclass has made me ‘feel more like myself’ than I have for a long time.

Participant feedback

Ngaropi Raumati (Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki), vivian Hutchinson (Community Taranaki) and Charissa Waerea (ACE Aotearoa) — pictured outside Te Raukura, Te Wharewaka o Pōneke, ACE National conference June 2021.

Photo credit: ACE Aotearoa

The Masterclass leads are careful not to claim praise for outcomes that have emerged for individuals who have been part of the Masterclass journey. They remain humble, and acknowledge that changes, activations, projects, and personal development belong to the participants, not them as individuals, or their organisations. Despite this, both feel a strong sense of positive community development in Taranaki because of the Masterclass process. Their success also formally recognised thorough the awarding of the 2020 ACE Aotearoa Annual Award for Community Programme of the year – Tangata Whenua.

An evolving bicultural approach

The Masterclass process, content and format has continued to evolve. A couple of years after the first conversations, Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki wanted to become involved, but to do it their way required a bicultural approach vivian says. “This was easily done due to some long-standing relationships, over several generations. The trust was already there for creative collaboration.”

Awhina speaks of the advancement of Māori and indigenous ideas of community development and active citizenship that has happened through conversations over time. For an organisation like Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki, it’s about walking in both worlds and having to translate concepts with a te ao Māori perspective. “This information wasn’t available at the beginning, it is content that we have had to think through, explore readings, look at other indigenous communities and land upon our own thinking”.

What’s changed?

You can’t operate in a community without being part of the community.

Awhina Cameron

Both vivian and Awhina enthusiastically explain that for them, the Masterclass has been the most profound, effective, and directly beneficial ‘professional development’ programme they have witnessed. Finding and opening-up space for deep conversations and reflection has led many participants to new insights on citizenship, belonging, cultural competence, assets that are latent in their communities and their own individual purpose and contribution to community. And for those working as service providers, the Masterclass has grown understanding about the need for people to be themselves, have space to think and find their purpose – that their work needs to be about more than just services says Awhina. “Having kaimahi, community members, clients and others all involved together in the Active Citizenship process, and as active citizens, thereafter, is contributing to the overall health and success of the community.”

Participants finish the Masterclass with an action plan for their own roles and direction as active citizens in the community. This has led to participants progressing a range of initiatives that hold meaning for them, from kaumatua group activities to mirimiri /massage for babies, to a community garden project, community gymnasium, and kapu korero sessions, where community members come together to practice their every day reo.

Sharing what’s been learned

There is tremendous knowledge held within the group and people were extremely generous in sharing their wisdom.

Masterclass participant

With Covid bringing a halt to running the Masterclass in person, the team has put their minds to other ways of sharing their knowledge.

Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki and Community Taranaki have developed a written guide about the Masterclass as a step towards sharing this knowledge with other communities. This extensive resource is available on their website and was supported by the Department of Internal Affairs. Awhina emphasises the importance of asking questions and engaging in conversation, and offers a way of approaching the guide – “Ask, where is the relevance of this thinking, particularly around Māori concepts?”

Alongside the Masterclass Guide, Ngaropi Raumati, Kuia and Director of Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki has created Te Kai a Te Rangatira (2020) video series based on her stretch conversations held in the Masterclass.

vivian has brought together a collection of essays on topics at the heart of Active Citizenship and published these into a book, How Communities Awaken — Some Conversations for Active Citizens (2021). The essays are freely available on the Community Taranaki website.

vivian’s advice for other communities looking to begin something similar is to make time and space to read and absorb the material. Like Awhina, he views the Taranaki Masterclass resources as a place to begin conversations and evolve from there. A useful start to creating your own Masterclass can be found in his paper, Some Elements of Design.

Get your thinking about Active Citizenship started!

Read the guide to the Taranaki Active Citizenship Masterclass

Watch Tū Tama Wahine o Taranaki’s “stretch” videos by Ngaropi Raumati which look at Active Citizenship from a Te Ao Māori lens

Read How Communities Awaken essays by vivian Hutchinson

In 2022, Inspiring Communities will share vivian’s essays on our social media. We are keen to open a wider national conversation about active citizenship, and ways to grow more of it across our communities. Please join us for this conversation!

In 2022, Inspiring Communities will share vivian’s essays on our social media. We are keen to open a wider national conversation about active citizenship, and ways to grow more of it across our communities. Please join us for this conversation! Like and follow our Facebook and LinkedIn pages and make sure you’re on our newsletter mailing list.

Inspiring Communities would like to thank Awhina Cameron and vivian Hutchinson for generosity of their time spent speaking with us for this story.

From small places come big things – The story of the Rakiura Museum

Rakiura (Stewart Island), is a beautiful, remote and virtually untouched part of Aotearoa. Surrounded by native bush, windswept beaches, rugged coastlines and rare wildlife, the place holds a strong attraction for both locals and visitors alike.

With only 400 permanent residents, the people of Rakiura often have to look inwards to get things done – and they do. Rakiura has a strong history of its community pulling together to make things happen. The development and building of the new Rakiura heritage centre which opened in December 2020 was no exception according to Rakiura Museum – Te Puka o te Waka building committee chairwoman Margaret Hopkins.

The Rakiura Museum had existed on the island since the 1960s. Home to a large collection of important items, it had undergone an extension in the 90s before it was decided that a brand-new building would be needed to house their expanding collection. A Trust was set up to manage this new build, bringing in people who were already trustees of the existing museum, council members, community board members and the Stewart Island Promotions Association.

The original Rakiura Museum.

Funding was their first challenge. Some of the members of the Trust had become adept at writing funding applications during the build of Rakiura Community Centre, a hugely successful community-led project in the 90s, and so were able to navigate the application process for the heritage centre. However, realising that the funds required would be much larger than that of the Community Centre, this time a project funding manager was engaged.

“You can only do so much and at times one or two of us were doing everything – It was exhausting in the early stages”

Trustees also approached anyone with a connection or link to Rakiura and discovered just how important this new museum was to people who had ancestry on the island. They received a lot of support and were surprised with the donations from people who only had tenuous connections to the island. When a final grant from the Ministry for Culture and Heritage was provided for $1.1 million, the Trust could finally put a spade into the ground and begin.

Building began in October 2019. An architecture firm and building company from the mainland were hired to create the structure; a triangular-shaped building that was reminiscent of a ship which was in keeping with the collection and the history of the island.

“It was very hands-on! The Trust was even baking for the builders, making sure they were kept happy through all the terrible South Island weather!”

A year on from when they first broke ground, the Rakiura heritage centre was finished on time and on budget.

The new Rakiura Museum

Drawing on Experience

Having worked on the Community Centre, Margaret was able to bring learnings from that project into the Rakiura heritage centre. At the top of this list was the importance of having a vision and knowing that with hard work, commitment and persistence – anything is possible.

As there often is with many large community projects, the Heritage Trust encountered their share of naysayers. A few permanent residents did not see the need for what they only saw as a tourist attraction and felt that the build was a waste of time and money. Rather than stop the project however, these negative comments made the Trust more determined to make it happen.

“To us, it felt justified, we know how important our history is for not only Southern New Zealand but for the whole country”

Trustees Anita Geeson, Bruce Ford & Margaret Hopkins at new museum site.

Having a good team with multiple skills and connections was also crucial. The important process of tendering for architects and building companies was done with care, ensuring that the professionals they engaged with understood how important the building would be when it came to representing the community and the history of the island.

Telling the Right Stories

Setting up the exhibition itself was a big step in getting the centre open and one that held many lessons for the Trust. This was one area where Margaret saw an increase in community members who were enthusiastic about getting involved. This provided an opportunity for many locals to see, touch and learn about the items that made up the fabric of their history.

“It gave locals a sense of ownership, especially when they could see their own stories being told.’

It was essential to the Trust that the right voices were heard when it came to telling the history of Māori settlement and habitation on Rakiura. For this, a local iwi committee was set up and engaged with to ensure that the items and stories they had on display correctly told this part of the Island’s history.

Margaret believes the exhibition is now more balanced because they have the correct stories, are able to focus on what brought people to Rakiura in the first place, and can celebrate the early communities who made Rakiura home.

Exhibition at the new Rakiura Museum.

The Importance of Mana

Despite the Island having a long history of Māori settlement, the culture and stories of local iwi were generally not well known or embraced. However, when the new Rakiura Museum finally opened with a pōwhiri, Gwen Neave who serves on the Toi Rakiura Arts Trust committee which commissioned and supported the Oral History project featured in the Museum, noted that it was a beautiful bridging moment for the community.

The pōwhiri was performed by a group, of which Gwen was a part of, that also included the local school and its students. While it was challenging to bring together and involved weeks of practice, Gwen saw the pōwhiri it as an opportunity to introduce this key cultural element at the perfect time.

‘It brought mana and gravitas to the occasion. It was moving for many there and well-received by those who witnessed it.’

A resident of Rakiura for 55 years, Gwen says the pōwhiri has had far-reaching effects on the island. Te Reo is now being taught to a class where they learn tikanga as well as the history of the island and about the mana whenua who live there. It is also being embraced in places like the local Four Square and in the school where Te Reo and English are used interchangeably.

There is a new dynamic to the community now, one that is more actively embracing biculturalism, the language and the deeper stories of this place. Gwen also notes that she’s loving seeing the way New Zealanders more broadly are coming of age with Te Reo and is so proud of the way that this small community at the bottom of the south is embracing this too.

Community Development is not always a linear path

As it is with any large-scale community project, challenges are always present. Whether it is the practical logistics of building in a remote location or negative comments from some quarters, there will undoubtedly be obstacles to overcome. Creating things for and in the community can at times be messy – it’s never a linear path.

Having not yet been open for a year, the heritage centre has already seen 14,000 visitors through the door. The centre has seen 25 school groups visit as well as strong support from both local and national visitors. To the community it is not only a source of pride and achievement but also a great drawcard to the Island, helping to bolster tourist numbers and support the economy of Rakiura.

Bruce Ford, Raylene Waddell, Jo Learmonth, Elaine Hamilton, Raja Hidzir, Julian O’Sullivan, Ian Sutherland, Margaret Hopkins

Margaret is also excited by the next generation of strong community-led leadership that’s emerging on Rakiura via Future Rakiura – a group formed in 2019 to encourage and build collaborative leadership skills amongst young people. As a mentor for this group herself, Margaret has seen them pull together and lead Waitangi Day celebrations, community get-togethers, and fundraisers for small community projects. Gwen also is a mentor for Future Rakira. Connections help to bind the community together, allowing them to create a unified focus when it comes to getting things done for the people who live there.

“When you come out the other end of a project like this, you realise that no matter where you live, or what resources you have at hand, if you have the vision and the drive to get it done – anything is possible”

Joy for Generations: Nurturing intergenerational connections

As the old proverb goes, it takes a village to raise a child. Having strong relationships and connections with people nearby who are young and old, contributes to children, young people and parents’ sense of belonging and safety. And this feeling goes both ways – all generations benefit from feeling connected with their community.

For those of us with our heart in transformational initiatives, Joy for Generations (JFG) is a story of building connections in local communities to bridge the gap between generations young and old. It’s about learning from one another, proactively counteracting loneliness, and reconnecting community.

Intergenerational connection and learning have always been a fundamental part of flourishing, thriving communities and cultures. Yet too often we divide our communities and activities up by our age.

Our young people are in schools, while more mature and ageing generations often now live in retirement communities or aged-care facilities. As a result, there is often little interaction between generations.

Joy for Generations’ story demonstrates the importance of building intergenerational wellbeing in place, reconnecting our young people with the learnings and love of those before them.

Building a community within a community.

Lucy Adlam is a self-starter. Working for a not-for-profit organisation that connected older people with services in their community, she was about to take maternity leave when she decided to spend two weeks in the call-centre before she left. Her experience there changed her.

“Some of the elderly people I spoke to said it was the first phone call they had received in months.”

Lucy decided that once her daughter was born, she’d start volunteering and spend time with seniors – knowing firsthand how important it is to involve everyone in community activities, to relieve isolation and improve their wellbeing.

Lucy began visiting rest homes. She remembers the memory of seeing people with no visitors, month in, month out.

“I still feel it all over my body.”

One day, Lucy noticed a woman lying still in her bed, unmoving. It wasn’t the first time she had noticed her. Not knowing what else to do, she carefully knocked and poked her head around the doorframe.

“Hello… there’s a baby here!”

The woman immediately rose up. She managed to climb out of bed, and she began to sing to make the baby laugh. It was as meaningful to Lucy as it was to her young daughter – with the older lady now dancing around the room.

This was the moment that the seed for Joy for Generations was planted.

Connection is essential to wellbeing.

Weaving together the strengths and relationships in your place.

With a young family, little time, and – at this point – no funding, Lucy knew it was important to first build from her own networks, relationships and local strengths. She began to engage the other new mothers within her antenatal groups.

Lucy began bringing more new mums to visit with the rest home, and they created intergenerational playgroups.

This point on their journey was about building relational capacity, and growing the group’s momentum through a sense of fulfilment. JFG wasn’t yet official, but Lucy’s connections within the community were growing.

Intergenerational play brings fun and connection to all involved.

Leaning in, and learning as you go.

Joy for Generations became official when Lucy moved to the Wairarapa.

By working to identify their kaupapa and vision of intergenerational wellbeing, Lucy was always learning.

“As much as we loved to see the playgroups grow, we noticed an imbalance of attendees, with rest homes having large groups of seniors and children feeling a little intimidated. This helped us to see that a core value in our groups was equal enjoyment for all generations.“

On the back of this learning, the group learnt to adapt their vision by focusing on how to bring the different generations together in a way that benefited the joy and learning for both generations.

JFG began teaching children more about older generations to make them feel more comfortable and increase their understanding of other generations. This helped children understand the meaning behind the intergenerational activities.

One of the most important parts of mindful development is to recognise that it’s easy to get busy with the ‘doing’, and not make time to reflect on what’s working, what’s not, and how to adapt.

Music workshop for the young and the young at heart.

Building momentum through collaboration and experiences.

Collaborating with diverse community groups and organisations Age Concern, Ka Pai Carterton and Neighbourhood Support, and connecting with the three district Councils in the region, JFG formalised their structure and set up a Board of Trustees to provide strategic guidance.

JFG organised a community hui (Wairarapa Children’s Day) and invited local kaumatua to share stories and crafts with children. Strengthening connections and relationships with local iwi was always a priority of this kaupapa.

“Maybe because it’s a small region, there is a strong sense of place and belonging here. Everyone just got involved. We only initiated the start and it grew into this wonderful thing.”

Poi workshops were held at the local primary school, and several rest homes brought residents to the school to participate. The only challenge was getting the seniors back to their rest home.

Sharing Joy” artworks created by local tamariki.

During Lockdown, JFG acquired some funding to create art packs for 50 families, sending the art out in collaboration with Age Concern.

“One older lady called me and told me just how much the artwork blew her away. She didn’t have any family or grandchildren around her. The young boy who created the artwork now calls that lovely lady his ‘NZ Grandmother’ – and they exchange art work and cards regularly. I mean, that is just one of those wonderful moments.”

A rally cry for more diverse funding models.

As JFG grew, so did its financial needs. In what is a familiar story for many grassroots community-led initiatives, their sustainability and impact rely on volunteers, on funding and in some cases, self-funding. More and more rest homes wanted to set up intergenerational playgroups, but this began taking more resources than JFG had to give.

Building relational capital, nurturing local relationships and developing adequate funding proposals all takes resource, capability and capacity that some locally-led initiatives don’t have to spare.

“As community-led initiatives continue to learn and develop as they go, it calls for funding models and procurement systems to do the same. One system does not fit all.”

Another JfG initiative, the Happy to Chat bench, invites people to connect and share a yarn.

Funds might run out, but the community never goes away.

Intergenerational practices provide a setting that can help to relieve isolation and involve people in activities that contribute to – and improve – the general health and wellbeing of our societies and of our families.

The relationships built, the learnings gathered, and the people who have now been connected and inspired by JFG continue to exist in the Wairarapa.

“There are a couple of other playgroups at rest homes around New Zealand, but no other organisation is focusing on intergenerational initiatives and connections. We’ve really tried to develop the intergenerational space here in New Zealand, and have been found online by groups in America and Asia who have contacted us for support. Some things work out, and others don’t. It’s all learning. People who want to better our communities, our tamariki, our elderly, will never go away.”

Lucy is pragmatic. She sees JFG as a pilot, and hopes that it will be an initiative that sprouts again inside and outside of the Wairarapa region, fostering age-inclusive communities all across Aotearoa.

If you’re keep to tap into Lucy’s experience and ideas on building intergenerational connections, you can contact her at lucy@joyforgenerations.org or through the website www.joyforgenerations.org.

Video: The Heathcote Village Project

10 years on from the tragic earthquakes that struck the Canterbury region, The Heathcote Village Project share their story from the epicentre of the quake, with a focus on the power of community when working from a strengths-based model.

“It’s that shift that is happening at a world-wide level of realising that we are living. Therefore we need to think in more of a living systems way. A dynamic way that allows for emergence and doesn’t go pre-prepared.”

Kidshub: Looking after our tamariki, whānau and community the CLD way.

Over the last two years the Christchurch Methodist Mission (CMM) Community Development team have worked alongside a group of whānau who are passionate about providing experiences and opportunities for their community. Together they have created the ‘Kidshub’ initiative in Linwood, Christchurch.

The Kidshub committee is now made up of 5 whānau leads and committed to providing low cost or no cost activities for whānau in the Linwood area. Building on the seed of an idea sown at a parents’ hui about five years ago, they have been busy organising community meetings and community events for their whānau, tamariki and the wider community.

With support from a CMM Development worker, a family worker from the Linwood Community Corner Trust, a Christchurch City Council advisor and Kim from the STEAM collective, the committee has organised a range of activities for the community during the school holidays. These activities all promote brain development and team building: they include art and craft, high tech days, maths exercises (using dragon cards in order to complete mathematical tasks in a fun way), engineering exercises, as well as bus trips to Victoria Park, Willow Bank and Spencer Park. Moreover, the committee also organised several community events throughout the year such as a kids market, Quiz night, neighbourhood BBQ, pizza nights and a light dance.

Fun for everyone at the Kidshub Activity Day 2019.

In February 2020, whānau and tamariki presented Kidshub to the Linwood Community Board, sharing their vision and goals: to give the tamariki the kind of experiences that they have been dreaming of, experiences that they wouldn’t normally have access to, and to enable whānau to share these experiences with their tamariki. The Kidshub committee envisions these experiences to come at little to no cost for whānau to ensure that tamariki have the highest possible likelihood of being able to participate.

Kidshub is all about fostering community connections in a neutral environment. A place to nurture whānau connections and to create a sense of belonging and bonding, with shared interactions and new experiences in a safe space for whānau to enjoy time together.

“We value the whānau being present at Kidshub so that these memories can be experienced and reminisced about together.”

Abbi, Kidshub parent leader

Key community-led learning from Kidshub:

In talking with the committee whānau about why they enjoy the Kidshub, they speak about the relationships they been able to build with the people whom they have met, and about having grown in confidence. The hope is that this will filter through to their tamariki to grow more confident and eventually become leaders in their local community. Kidshub is nurturing this growth and providing opportunities for leaders to grow.

Gardening is a great way to learn for the tamariki.

The success of the Kidshub initiative points to the role that the following key principles of community-led development play in community projects:

The importance of place and a sense of belonging

There is a long term commitment to the mahi because the whānau feel a strong sense of connection to, and ownership of the places and spaces occupied. Working in collaboration with the neighbourhood and making sure everyone felt safe and respected, the committee cleaned up the section, removed rubbish, and turned it into a space that was safe and safe for everyone to enjoy.

Belonging, community and play are represented in the Kidshub logo.

Taking the time to listen and understand local voices

“We listened, opened up possibilities, we took our time because we didn’t know what would happen.”

Anne Gibling, CMM Community Development Worker

The committee dedicated a lot of time to building trusting relationships with the whanau in their community, and involved them in every step of the process, starting from scratch and finding resources needed to create a space where everyone felt heard, understood and had their needs met. It is from the shared experience and active listening and engagement that trust, respect and relationships can grow.

“The way we talk about others is important in shaping how we connect.”

Anne Gibling

Local leadership and learning by doing

The driving power behind Kidshub was the leadership of the four key women and their wishes for their children. Putting these ideas into action and reaching out for support where they needed it enabled them to build relationships with people in the wider community, even with those whom they never imagined they would be able to connect with. They were able to build trust through making the commitment to show up, listen and act on what they promised. Growing and learning along the way, there is not set-in-stone agenda, the whānau are shaping next steps as they go along – together with their community.

For more information on the Kidshub initiative, please email Anne Gibling, Christchurch Methodist Mission.

Punching above its weight: The revitalisation of Reefton.

Similar to many other small towns across Aotearoa, the people of the West Coast township of Reefton have been working hard to revive their town and restore not just its history but its future as well. In early 2019, key economic indicators demonstrated that what locals had intuitively felt was indeed happening: by March, the GDP in Reefton had grown by 14.6% and its labour market had grown by 14.5%, compared to the national average of 3% and 1.9%.

The decades of work to revive their town’s fortunes were paying off!

Reefton’s beautifully restored shop fronts on the main street.

A real boomtown during the heydays of hard rock underground gold and subsequent coal mining (with 2,000,000oz of gold extracted between 1870 and 1951!), Reefton, like many small regional towns, went into a significant decline during the last decades of the 20th century, struggling with a changing economy and increased privatisation. The closure of major Government departments such as the New Zealand Forest Service and Railways resulted in a drastic shortage of local work opportunities and consequent rise in unemployment in the area.

But Reefton’s locals are fiercely loyal to their place and have worked together to transform Reefton not only into a popular tourist destination, but also attractive to entrepreneurial investors and new residents seeking a lifestyle change.

Shared local vision grows collaborative local leadership

PAUL THOMAS

“You need catalysts to take communities forward.”

The revitalisation of Reefton into a contemporary, progressive town can be attributed to a mix of external backing and community-led initiatives, as well as the dedication of passionate individuals, who together have produced remarkable outcomes for their town. In his position as manager for the Department of Conservation, Paul Thomas moved to Reefton in 1990 and saw the potential of Reefton’s unique location and history despite its then rather impoverished state. He’s been a hard-working advocate for the town ever since: Paul was part of the first core group of locals pushing for change, seeing an opportunity to leverage Reefton’s unique environment and rich heritage history. Proudly known locally as the “Town of Light”, many people may not realise that the Reefton was actually the first town in the Southern Hemisphere to have a public and reticulated supply of electricity in 1888, even before London and New York!

Reefton’s rich heritage is ever present.

“Town revitalisation is an organic process,” says Paul. “You need catalysts to get things going. One of the first catalysts for Reefton was developing a community vision back in 1996.”

Around 90 people came together for the “Community Revival Workshop”, and collectively put together a list of Reefton’s best attributes. This list evolved into the “Reefton Revival Plan” which proposed ways forward to build from the town’s strengths and assets. It was widely distributed within the community in the hope of getting as many people on board as possible.

The Reefton Revival group aimed to revive and celebrate Reefton’s goldfields character from the 1870s. One of the first big initiatives, straight out of the workshop, was to redesign the proposed new addition of a library to the Buller District Council’s service centre – despite significant pushback from the Council and local residents, the group managed to move forward with their vision for the new building to reflect the distinctive heritage look and wooden architecture of Reefton’s original buildings – despite a more modern build.

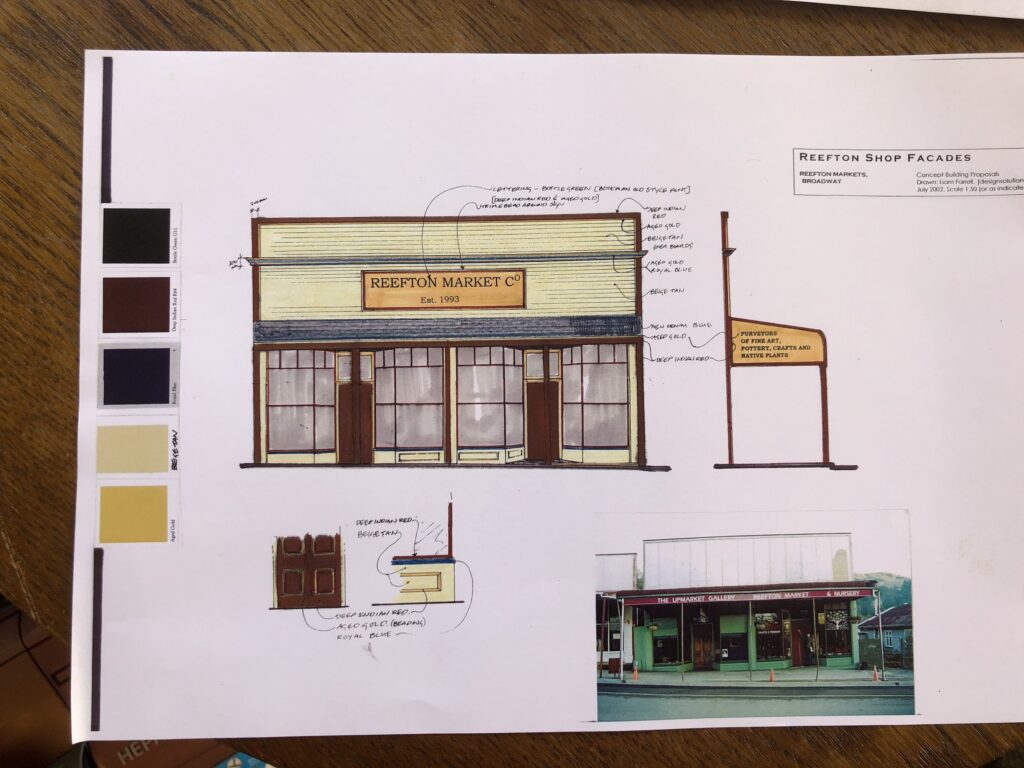

In 2002 the Reefton ‘Shop Front Project’ focused on further bringing back the distinctive character of the town’s main street. “This project was very innovative and transformational for Reefton,” says Paul. Led by the community’s town promotions organisation, the Inangahua Tourism Promotions (ITP) / Reefton Promotions Group, the Shop Front Project group used concept architectural drawings of Reefton’s main street buildings by local landscape architect Liam Farrell to illustrate how they would look refurbished, and together settled on a heritage colour scheme.

The Reefton Tearooms and Bakery are one of the beautifully restored cafés in town.

With the vision in place, the Group applied for the necessary funds from Development West Coast (DWC) to restore several shop fronts on Reefton’s main street. The ITP / Reefton Promotions Group was responsible for managing the loan received from DWC, and to on-loan the funds to individual business owners to restore their facades. “The project was a significant success story for DWC and it was a transformational project for the town,” reflects Paul. “With each phase of the project, we saw more and more buildings restored, as individual homeowners joined in and applied for finance to also fix and paint their buildings.” The cumulative result over the course of a decade created to a substantial lift in the main street’s appearance, which in turn resulted in a great sense of pride in their place for the locals, and in a new surge of visitors who were captivated by the charm of the place.

More than 20 years on, further restorations of Reefton’s building stay true to this colour palette which has resulted in a vibrant and authentic Reefton town centre filled with busy shops, cafes and art galleries. It is this distinctive look and celebration of Reefton’s heritage that really sets the small town apart from others and is not only a source of pride for the locals, but also underpins the town’s plan to secure long-term economic growth and sustainability. This vision has also attracted new entrepreneurs, investors and visitors alike.

Paul Thomas on Upper Broadway where a significant first phase of the Reefton Shop Front Project took place, including the Hale Gallery on the left.

Drawings for the Reefton Market’s transformation into Hale Gallery.

“The investment by DWC into Reefton through the shop front project was an innovative model, a leap of faith at the time for community-led economic development, and it has created immeasurable results that have ensured the town’s long-term sustainability,” Paul says.

Working with diverse groups, ideas and skills

“What has happened with the shop fronts since the early 2000s has been sensational. The face of the town has now changed – now we have a town that we are all very proud of.”

HELEN MCKENZIE

Helen McKenzie grew up in Reefton before moving away in her twenties, and recalls that during her frequent visits back, Reefton was “a busy little town, but things were starting to look a little sad”. Returning home about six years ago, Helen now describes her hometown as being back to its old buzz and attracting new residents with its restored heritage buildings and beautiful surroundings: “People often comment that ‘it’s just like Arrowtown before it got too developed’.”

Helen now manages the local Dawson’s Hotel and reflects that the secret to the town’s resilience lies in its many offerings – unlike other heritage towns, it does not solely rely on tourism. Gold and coal mining remain critically important for local employment, as well as the local dairy industry, the native timber mill and the service sector supporting these industries.

Mountain biking plays a big role in Reefton, for locals and visitors alike.

“It’s all about balance. You need socio-economic stability, but you also need to be mindful of the needs of the community,” notes Helen with a nod to many Reefton residents’ wish to maintain the town’s small size and quiet lifestyle despite its economic growth.

“Where else in the world, after a day of there not being a carpark to be had, can I have a chat in the middle of the main road at 5pm in the afternoon? That’s exactly the kind of town I want to live in.”

JOHN BOUGEN

Paul agrees that it’s the diversity of businesses, skills and ideas that makes the town sustainable, plus the variety of groups and skill sets that are coming together to push forward ideas and projects, citing the current restoration of the community theatre, funded by the Buller District Council as one example. John Bougen, another local resident deeply invested in Reefton’s revival, adds that this fund has also extended to the Reefton Racecourse where the Grandstand and Tearooms are receiving further much needed refurbishment, as well as the restoration of the historically important Railway Station and Oddfellows Hall. Furthermore, another recently received substantial grant will see the Strand Revitalization Project completed, which was initiated 25 years ago and will finally link the town to the Inangahua River on which it was founded.

“It’s a knock-on effect. Once people see that something is working, they want to be part of the success,” says John. “And it’s amazing how you can find the funds you need once you have proven you are actually doing good things for the community.”

Building from strengths

“Authenticity is fuelling Reefton’s future.”

NZ BUSINESS MAGAZINE, DECEMBER 2019

It’s the entrepreneurial spirit of locals and newcomers alike that has been another catalyst in Reefton’s return to vibrancy, agree Helen, Paul and John. One example of a home-made success is the popular Reefton Distilling Co which, founded by another returnee Reeftonian, Patsy Bass, has gained an excellent reputation, and business success, selling their goods both nationally and internationally.

The Reefton Distilling Co is housed in one of Reefton’s original buildings which has been carefully restored to accommodate the working distillery, tasting bar and retail store.

Another is John himself: the self-made businessman turned Buller District Councillor who fell in love with the place and its people when he moved to Reefton five years ago. “People here on the West Coast are so friendly and have such a positive, cheery disposition. Things are possible here, people are open to ideas.”

Humble about his own contributions to Reefton’s recovered economy, John is quick to point out that the community has always been the main driver behind returning Reefton to its old glory:

“The fire has been lit a long time ago -all I have done in the last five years is put a bit more petrol on.”

JOHN BOUGEN

John’s can-do attitude and investment in the restoration and re-purposing of heritage buildings in town have continued on from the Shop Front Project to others, like the repainting of the old mining school, the complete rebuild of the original gaol, along with a number of shops on Broadway, Reefton’s main street. These heritage buildings are now a stunning backdrop to every visitor’s holiday photos and have moreover created local jobs and sparked ideas for new ventures, from the likes of another local who is now building tiny houses at Reefton’s old mill, and Andy and Sarah Parker who have boldly and faithfully restored the old Knox Church.

The restored School of Mines building.

“Reefton is now thriving and people are committed to keeping this going,” says Paul. John adds that the shared vision is very much to enable and support ideas to keep that momentum going: “The great thing about the West Coast is that you just do it. We have everything here – opportunities are abundant.”

And it’s not just business owners who have been ramping up the pace in Reefton. Local artists and artisans have been busy creating a burgeoning creative and social hub. Their contribution is apparent all over town, including the Friday nights at the Workingmen’s Club which now hosts a vibrant scene. The local galleries have never been busier, attracting more and more visitors. “Reefton has become a real go-to place,” agree John and Paul.

A long-term vision for lasting change

This is also reflected in local government’s attitude towards supporting bigger projects and the continuous building up of skills amongst the community. “There is lots of enthusiasm around the Council table,” says John. “Now is really Reefton’s time.” He adds that while Reefton has a core team of leaders doing a great job at working on the ongoing development of their town, they are also mindful to “leave the door open for other people to come in”.

“There’s always been different key people at different times who have carried things through – everyone brings a different skill to the table.”

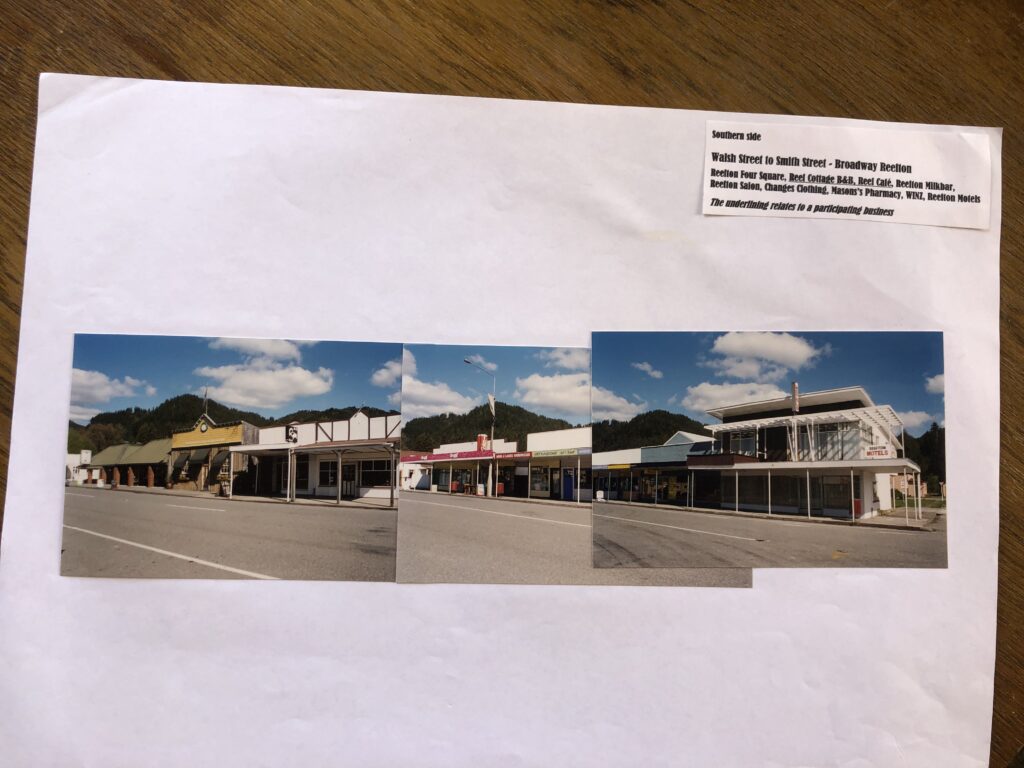

Reefton’s Walsh to Smith Street in 2002.

The same area, almost 20 years later: Walsh to Smith Street in 2020.

Paul adds that there has always been real stand-outs among the people who have dedicated their time and energy to their community: “It’s often me who gets interviewed for the papers but without people like Ronnie Buckman for example, we could not have achieved what we have. Ronnie has been pulling cords behind the scenes all these years. Not only was she our first Visitor Centre Manager back in the 90ies and then stepped into promoting our town and cause, she’s been essential to building the relationships between the community and the funding agencies. She’s a local, a real ‘West Coaster’, she’s been our connector for the Revival Project all along.”

All agree that everyone needs to be committed to the long haul – maintaining a flourishing community and a buzzing town is an ongoing project, not one that’s finished after a few years work. Working together as a community is all about finding the right balance between people’s needs and wishes for their town, and the economic realities of keeping everyone in jobs and business. Community and local business development must go hand in hand.

“It’s important to have these constant conversations, is it working, or is it not working? And making adjustments as you go along.”

PAUL THOMAS

Done with being done to: Meremere’s journey to confident local leadership

Located about halfway between Auckland and Hamilton, just off the State Highway 1, the township of Meremere had struggled to revive its heyday’s spark after the Meremere power plant shut down in 1991 and many residents lost their employment. A sense of feeling forgotten and cut-off created frustration among the residents, and for several years, initiatives by different providers and ‘outside’ organisations had only temporary effects – one sentiment shared by the community was that they felt “done with being done to”.

Growing Collaborative Local leadership

With initial support from the local Council, the Ministry of Social Development, and the Department of Internal Affairs, a group of local residents took matters into their own hands and formed the Meremere Community Development Group in 2011. Thanks some initial grass roots funding like the Community Organisation Grants Scheme (COGS), the group gained momentum and led their first own community projects – these successes built the foundation and vision that then led to the establishment of the Meremere Community Development Committee Inc. in 2013.

Ben Brown, Secretary of the Development Committee, describes the committee as a core group of people that acts as “a sort of super-glue” for the community: “We look after the community-led, the community-based stuff, we help out with people’s community development aspirations.” Establishing this group and voicing the community’s hopes and needs were among the key first steps for the locals to step into their own power to activate change in Meremere.

“We are here for the community-led stuff, for helping to achieve our community’s development aspirations.”

Ben Brown

Read more

“The key thing has been growing a sense of empowerment within the community,” says Mary Wilson, who in her position as Community Advisor for the Department of Internal Affairs, has actively supported the Meremere community on this path.

“With community development, it’s important that supporters also know when to step back and let them forge their own path. Access to funding and resources is only the enabler – the community has to own it and be the driver. For a number of years, Meremere had been ‘done to‘ – they needed time and support to take the lead themselves and do things at their own pace. My role initially was to build their confidence and ability, i.e. the ‘how to’. And look at them now!”

“Funding is only the enabler – the community has to be the driver.”

Mary Wilson, Community Advisor, DIA

Pulling together strength and building a shared vision

Run entirely by a small team of volunteers, the Meremere Community Development Committee is now often found pulling together funding for community events, youth activities and leading projects to add to the town’s infrastructure.

Their first major effort was the design and establishment of a new multi-purpose community hall in 2015, which has been a crown jewel of achievement and a much loved new local asset.

The purpose-built Meremere community hall.

Here, the DIA Community Advisor acted as a broker with the Council to bring the required funding together (Trust Waikato, the NZ Lottery Grants Board and the WEL Energy Trust gave their support) to support the community in developing their vision for their hall – which then drove the project.

“Our hall has been built by locals for locals – people have a lot of respect for it. It’s really an amazing resource for us all – I think any community would love to have a hall this grand,” Ben says of the sense of pride that the new hall has instilled in the community.

Going from being a community that felt left behind to an empowered one that takes matters into their own hands, has been a big learning curve for everyone involved, agree Mary and Sarah Gibb, Community Advisor for Community Waikato. “Now that strong relationships are in place and people know who to reach out to, there is so much more initiative to make things happen. People have learnt that it is ok to ask for help, and that they also have the ability to do things themselves.”

The community hall was transformed into a warehouse during Lockdown – the Development Committee worked together every day to help their community.

This doesn’t mean that there are no more struggles. Both Mary and Sarah point out that making sure everyone feels heard and involved in the community’s future remains a work in progress. “With new people come new ideas and, of course, robust discussions. This is healthy, and all part of the learning and growth,” describes Mary, noting that community development is all about the journey, not the destination.

“It’s about the journey, not the destination.”

Mary Wilson, Community Advisor

Learning by doing – and doing by collaboration

Sarah says that since the Community Development Committee’s establishment, all the agencies involved in supporting the community have welcomed the collaboration and collective achievements in Meremere. “What they achieved during Covid-19 this year was truly exceptional.” In a huge communal effort, the Committee managed to pull together resources from funders, agencies, charitable organisations like the Salvation Army and the regional kai rescue, as well as local businesses and growers, to deliver over 2,000 food and sanitation packs to their community. The fact that Meremere did this for Meremere was also noted with pride by many local residents.

Ben Brown and his fellow committee members did not wait for people to call out for help – they “just went ahead” to ensure their community remained safe and well. Asked about how they quickly pivoted from finding funders to build a skate park (which was made possible thanks to the support of Waikato District Council) to organising truckloads of food and sanitation supplies, Ben shrugs, “It’s a different kettle of fish. We were thrown in at the deep end, and I reckon we swam pretty well.”

Ben Brown and his truck filled with supplies to sort into food parcels for the community.

And this attitude has not changed since the end of Lockdown.

“There are still a lot of people in genuine need for support here,” says Ben. “One of the great things that has come out of our efforts is that we now have a permanent Food Bank in Meremere. It’s run by locals for locals, all volunteers – people here have a lot of respect for it.” Also underway is a community food pantry – again, a network of different organisations was mobilised to pull together resources and workforce to make this happen: the TK Mens Shed built the actual pantry while the produce for it will come from the local community garden.

From immediate response to lasting change

“Going from an emergency response to establishing a permanent social service is possibly the best result for us,” reflects Ben about the Food Bank and Pantry. “There is always a silver lining. Everyone has become much closer through this experience. We now have a much better understanding of our community and who they are, and the whole committee is well known in the community.”

“Meremere will continue to see lots more change, but we will continue our community effort. It’s a wonderful place to live.”

Ben Brown, Secretary, Meremere community development committee

Looking to the future, there’s shared agreement that the “Meremere pride” is clearly returning.

Ben Brown says that the silver lining of Lockdown was definitely that everyone in the community grew a lot closer together. “We are a tight-knit community. We know and help each other.”

“Meremere is in a much better position now, and more and more skilled people are moving to the community. This was evident in the opening of the new library last year: there was a great sense of pride all around – young families, dads pushing prams, the Mayor, everyone was engaged and was so proud,” Mary reflects on the Meremere community’s regained capability to drive their own success. “People are keen to leave a legacy for future generations.”

Ben agrees: “We will continue with our effort here as we are for eternity, until it’s not needed anymore. Meremere will continue to see a lot more change, but those hundred phone calls have been made now – we know we can get help when and where we need it. Meremere is such a tight-knit community. We know each other, and we help each other. It’s a wonderful place to live.”