Thriving in the unlikeliest of locations: Waimamaku’s Story

When the factory shut down in the 70’s, hundreds of locals lost their jobs. With no other major employment opportunities, the town experienced a steep financial decline. Although over 40 years ago, the closing of the factory highlighted just how tenuous the employment situation in remote rural towns can be and how vital local support is when it comes to revitalising a community.

Waimamaku is home to all of 500 odd residents, and within the walls of the old cheese fridge, they are able to find a source of social cohesion. A place where locals can meet, get to know one another, discuss what they feel their community needs, and learn new skills.

From the most humble of places, locals receive computer-related assistance, get help with funding and admin issues, enrol in workshops, and share skills that have been identified as important to the community. Educational opportunities are always present, along with after school activities and resource centre volunteers who take people to town to run errands once a month.

“We provide workshops to enhance skills so that people here are given a pathway to employment. For example, we have workshops such as ‘Potions and Lotions’ for locals who are interested in getting into cottage industries. They can make their own soaps and then sell them at the monthly market alongside other local products and produce.” COURTNEY, PROJECT COORDINATOR, WEKAWEKA VALLEY COMMUNITY TRUST.

“We had a number of community meetings where we used paper and pens and mapped out our collective vision for Waimamaku.”

Grow from shared local visions

The Waimamaku community are working toward a strong collective vision for their home. The community got together to decide what they felt Waimamaku needed. Collectively, they mapped out their vision and made an application to the Department of Internal Affairs’ Community-led Development Programme. A partnership with the DIA has brought funding to focus on the needs and aspirations of the community, as well as the supporting the operating costs of the resource centre.

Build from strengths

Due to its distance from other main centres in Aotearoa, their place continues to face limited job opportunities, a lack of options to train and upskill, and a shortage in public transport services. But locals feel many of these issues can be addressed through connection and collaboration. Meetings, dinners and get-togethers are set up to help locals share their own aspirations for their community. The community understands that if they are all on the same page, they are able to harness this power as a collective group to make change for the better.

Without the shared skills of the Waimamaku community, the centre may not have had such a strong revival. The centre draws on these strengths, fostering environments in which people can learn from their neighbours. A recent example is when a community member came to the centre to discuss the expenses of installing a new septic tank. This led to the centre engaging with a local who agreed to run a workshop, teaching people how to build their own composting toilet.

“In Waimamaku there are many different individuals with amazing skills and knowledge. Here at the Resource Centre, we can be the connector for these individuals.”

Work with diverse people and sectors

The Wekaweka Valley Community Trust also supports a number of other unincorporated groups in the valley by assisting them and holding their funds. For example, the community garden group can apply for funding under the trust as well as a social sports club and a health initiative. All ideas and groups are welcome with locals recently setting up a soft plastics recycling, a pataka kai food pantry and a seed swap.

Learn by doing

When it comes to community-led development, you can try to plan ahead as much as you like, but there is no blueprint for things like this. Each community is different with varying needs.

“There is a bit of a strategic plan within the centre but a lot of the mahi is done by people getting together and simply just doing it. There doesn’t have to be too much overthinking. All you need is a few passionate people who come up with an idea, draw the community around them, and get things happening organically.”

Looking ahead, there will be more educational opportunities within the centre on the horizon. At the moment they are working with NorthTec, a tertiary provider in northern Aotearoa, to bring computer classes to the community. And as invaluable as their humble meeting place has been, they would love a new, larger facility for their growing needs. Something that the centre and their community are working towards, together.

The floors may be a little uneven, the walls lacking windows and there are a few leaks here and there but it is the community-led mahi that happens within the old cheese fridge that matters, proving that it’s not the place but the people around you that give the community heart.

Facebook: @WaimamakuResourceCentre

Joy for Generations: Nurturing intergenerational connections

As the old proverb goes, it takes a village to raise a child. Having strong relationships and connections with people nearby who are young and old, contributes to children, young people and parents’ sense of belonging and safety. And this feeling goes both ways – all generations benefit from feeling connected with their community.

For those of us with our heart in transformational initiatives, Joy for Generations (JFG) is a story of building connections in local communities to bridge the gap between generations young and old. It’s about learning from one another, proactively counteracting loneliness, and reconnecting community.

Intergenerational connection and learning have always been a fundamental part of flourishing, thriving communities and cultures. Yet too often we divide our communities and activities up by our age.

Our young people are in schools, while more mature and ageing generations often now live in retirement communities or aged-care facilities. As a result, there is often little interaction between generations.

Joy for Generations’ story demonstrates the importance of building intergenerational wellbeing in place, reconnecting our young people with the learnings and love of those before them.

Building a community within a community.

Lucy Adlam is a self-starter. Working for a not-for-profit organisation that connected older people with services in their community, she was about to take maternity leave when she decided to spend two weeks in the call-centre before she left. Her experience there changed her.

“Some of the elderly people I spoke to said it was the first phone call they had received in months.”

Lucy decided that once her daughter was born, she’d start volunteering and spend time with seniors – knowing firsthand how important it is to involve everyone in community activities, to relieve isolation and improve their wellbeing.

Lucy began visiting rest homes. She remembers the memory of seeing people with no visitors, month in, month out.

“I still feel it all over my body.”

One day, Lucy noticed a woman lying still in her bed, unmoving. It wasn’t the first time she had noticed her. Not knowing what else to do, she carefully knocked and poked her head around the doorframe.

“Hello… there’s a baby here!”

The woman immediately rose up. She managed to climb out of bed, and she began to sing to make the baby laugh. It was as meaningful to Lucy as it was to her young daughter – with the older lady now dancing around the room.

This was the moment that the seed for Joy for Generations was planted.

Connection is essential to wellbeing.

Weaving together the strengths and relationships in your place.

With a young family, little time, and – at this point – no funding, Lucy knew it was important to first build from her own networks, relationships and local strengths. She began to engage the other new mothers within her antenatal groups.

Lucy began bringing more new mums to visit with the rest home, and they created intergenerational playgroups.

This point on their journey was about building relational capacity, and growing the group’s momentum through a sense of fulfilment. JFG wasn’t yet official, but Lucy’s connections within the community were growing.

Intergenerational play brings fun and connection to all involved.

Leaning in, and learning as you go.

Joy for Generations became official when Lucy moved to the Wairarapa.

By working to identify their kaupapa and vision of intergenerational wellbeing, Lucy was always learning.

“As much as we loved to see the playgroups grow, we noticed an imbalance of attendees, with rest homes having large groups of seniors and children feeling a little intimidated. This helped us to see that a core value in our groups was equal enjoyment for all generations.“

On the back of this learning, the group learnt to adapt their vision by focusing on how to bring the different generations together in a way that benefited the joy and learning for both generations.

JFG began teaching children more about older generations to make them feel more comfortable and increase their understanding of other generations. This helped children understand the meaning behind the intergenerational activities.

One of the most important parts of mindful development is to recognise that it’s easy to get busy with the ‘doing’, and not make time to reflect on what’s working, what’s not, and how to adapt.

Music workshop for the young and the young at heart.

Building momentum through collaboration and experiences.

Collaborating with diverse community groups and organisations Age Concern, Ka Pai Carterton and Neighbourhood Support, and connecting with the three district Councils in the region, JFG formalised their structure and set up a Board of Trustees to provide strategic guidance.

JFG organised a community hui (Wairarapa Children’s Day) and invited local kaumatua to share stories and crafts with children. Strengthening connections and relationships with local iwi was always a priority of this kaupapa.

“Maybe because it’s a small region, there is a strong sense of place and belonging here. Everyone just got involved. We only initiated the start and it grew into this wonderful thing.”

Poi workshops were held at the local primary school, and several rest homes brought residents to the school to participate. The only challenge was getting the seniors back to their rest home.

Sharing Joy” artworks created by local tamariki.

During Lockdown, JFG acquired some funding to create art packs for 50 families, sending the art out in collaboration with Age Concern.

“One older lady called me and told me just how much the artwork blew her away. She didn’t have any family or grandchildren around her. The young boy who created the artwork now calls that lovely lady his ‘NZ Grandmother’ – and they exchange art work and cards regularly. I mean, that is just one of those wonderful moments.”

A rally cry for more diverse funding models.

As JFG grew, so did its financial needs. In what is a familiar story for many grassroots community-led initiatives, their sustainability and impact rely on volunteers, on funding and in some cases, self-funding. More and more rest homes wanted to set up intergenerational playgroups, but this began taking more resources than JFG had to give.

Building relational capital, nurturing local relationships and developing adequate funding proposals all takes resource, capability and capacity that some locally-led initiatives don’t have to spare.

“As community-led initiatives continue to learn and develop as they go, it calls for funding models and procurement systems to do the same. One system does not fit all.”

Another JfG initiative, the Happy to Chat bench, invites people to connect and share a yarn.

Funds might run out, but the community never goes away.

Intergenerational practices provide a setting that can help to relieve isolation and involve people in activities that contribute to – and improve – the general health and wellbeing of our societies and of our families.

The relationships built, the learnings gathered, and the people who have now been connected and inspired by JFG continue to exist in the Wairarapa.

“There are a couple of other playgroups at rest homes around New Zealand, but no other organisation is focusing on intergenerational initiatives and connections. We’ve really tried to develop the intergenerational space here in New Zealand, and have been found online by groups in America and Asia who have contacted us for support. Some things work out, and others don’t. It’s all learning. People who want to better our communities, our tamariki, our elderly, will never go away.”

Lucy is pragmatic. She sees JFG as a pilot, and hopes that it will be an initiative that sprouts again inside and outside of the Wairarapa region, fostering age-inclusive communities all across Aotearoa.

If you’re keep to tap into Lucy’s experience and ideas on building intergenerational connections, you can contact her at lucy@joyforgenerations.org or through the website www.joyforgenerations.org.

Video: The Heathcote Village Project

10 years on from the tragic earthquakes that struck the Canterbury region, The Heathcote Village Project share their story from the epicentre of the quake, with a focus on the power of community when working from a strengths-based model.

“It’s that shift that is happening at a world-wide level of realising that we are living. Therefore we need to think in more of a living systems way. A dynamic way that allows for emergence and doesn’t go pre-prepared.”

Kidshub: Looking after our tamariki, whānau and community the CLD way.

Over the last two years the Christchurch Methodist Mission (CMM) Community Development team have worked alongside a group of whānau who are passionate about providing experiences and opportunities for their community. Together they have created the ‘Kidshub’ initiative in Linwood, Christchurch.

The Kidshub committee is now made up of 5 whānau leads and committed to providing low cost or no cost activities for whānau in the Linwood area. Building on the seed of an idea sown at a parents’ hui about five years ago, they have been busy organising community meetings and community events for their whānau, tamariki and the wider community.

With support from a CMM Development worker, a family worker from the Linwood Community Corner Trust, a Christchurch City Council advisor and Kim from the STEAM collective, the committee has organised a range of activities for the community during the school holidays. These activities all promote brain development and team building: they include art and craft, high tech days, maths exercises (using dragon cards in order to complete mathematical tasks in a fun way), engineering exercises, as well as bus trips to Victoria Park, Willow Bank and Spencer Park. Moreover, the committee also organised several community events throughout the year such as a kids market, Quiz night, neighbourhood BBQ, pizza nights and a light dance.

Fun for everyone at the Kidshub Activity Day 2019.

In February 2020, whānau and tamariki presented Kidshub to the Linwood Community Board, sharing their vision and goals: to give the tamariki the kind of experiences that they have been dreaming of, experiences that they wouldn’t normally have access to, and to enable whānau to share these experiences with their tamariki. The Kidshub committee envisions these experiences to come at little to no cost for whānau to ensure that tamariki have the highest possible likelihood of being able to participate.

Kidshub is all about fostering community connections in a neutral environment. A place to nurture whānau connections and to create a sense of belonging and bonding, with shared interactions and new experiences in a safe space for whānau to enjoy time together.

“We value the whānau being present at Kidshub so that these memories can be experienced and reminisced about together.”

Abbi, Kidshub parent leader

Key community-led learning from Kidshub:

In talking with the committee whānau about why they enjoy the Kidshub, they speak about the relationships they been able to build with the people whom they have met, and about having grown in confidence. The hope is that this will filter through to their tamariki to grow more confident and eventually become leaders in their local community. Kidshub is nurturing this growth and providing opportunities for leaders to grow.

Gardening is a great way to learn for the tamariki.

The success of the Kidshub initiative points to the role that the following key principles of community-led development play in community projects:

The importance of place and a sense of belonging

There is a long term commitment to the mahi because the whānau feel a strong sense of connection to, and ownership of the places and spaces occupied. Working in collaboration with the neighbourhood and making sure everyone felt safe and respected, the committee cleaned up the section, removed rubbish, and turned it into a space that was safe and safe for everyone to enjoy.

Belonging, community and play are represented in the Kidshub logo.

Taking the time to listen and understand local voices

“We listened, opened up possibilities, we took our time because we didn’t know what would happen.”

Anne Gibling, CMM Community Development Worker

The committee dedicated a lot of time to building trusting relationships with the whanau in their community, and involved them in every step of the process, starting from scratch and finding resources needed to create a space where everyone felt heard, understood and had their needs met. It is from the shared experience and active listening and engagement that trust, respect and relationships can grow.

“The way we talk about others is important in shaping how we connect.”

Anne Gibling

Local leadership and learning by doing

The driving power behind Kidshub was the leadership of the four key women and their wishes for their children. Putting these ideas into action and reaching out for support where they needed it enabled them to build relationships with people in the wider community, even with those whom they never imagined they would be able to connect with. They were able to build trust through making the commitment to show up, listen and act on what they promised. Growing and learning along the way, there is not set-in-stone agenda, the whānau are shaping next steps as they go along – together with their community.

For more information on the Kidshub initiative, please email Anne Gibling, Christchurch Methodist Mission.

Punching above its weight: The revitalisation of Reefton.

Similar to many other small towns across Aotearoa, the people of the West Coast township of Reefton have been working hard to revive their town and restore not just its history but its future as well. In early 2019, key economic indicators demonstrated that what locals had intuitively felt was indeed happening: by March, the GDP in Reefton had grown by 14.6% and its labour market had grown by 14.5%, compared to the national average of 3% and 1.9%.

The decades of work to revive their town’s fortunes were paying off!

Reefton’s beautifully restored shop fronts on the main street.

A real boomtown during the heydays of hard rock underground gold and subsequent coal mining (with 2,000,000oz of gold extracted between 1870 and 1951!), Reefton, like many small regional towns, went into a significant decline during the last decades of the 20th century, struggling with a changing economy and increased privatisation. The closure of major Government departments such as the New Zealand Forest Service and Railways resulted in a drastic shortage of local work opportunities and consequent rise in unemployment in the area.

But Reefton’s locals are fiercely loyal to their place and have worked together to transform Reefton not only into a popular tourist destination, but also attractive to entrepreneurial investors and new residents seeking a lifestyle change.

Shared local vision grows collaborative local leadership

PAUL THOMAS

“You need catalysts to take communities forward.”

The revitalisation of Reefton into a contemporary, progressive town can be attributed to a mix of external backing and community-led initiatives, as well as the dedication of passionate individuals, who together have produced remarkable outcomes for their town. In his position as manager for the Department of Conservation, Paul Thomas moved to Reefton in 1990 and saw the potential of Reefton’s unique location and history despite its then rather impoverished state. He’s been a hard-working advocate for the town ever since: Paul was part of the first core group of locals pushing for change, seeing an opportunity to leverage Reefton’s unique environment and rich heritage history. Proudly known locally as the “Town of Light”, many people may not realise that the Reefton was actually the first town in the Southern Hemisphere to have a public and reticulated supply of electricity in 1888, even before London and New York!

Reefton’s rich heritage is ever present.

Read more

“Town revitalisation is an organic process,” says Paul. “You need catalysts to get things going. One of the first catalysts for Reefton was developing a community vision back in 1996.”

Around 90 people came together for the “Community Revival Workshop”, and collectively put together a list of Reefton’s best attributes. This list evolved into the “Reefton Revival Plan” which proposed ways forward to build from the town’s strengths and assets. It was widely distributed within the community in the hope of getting as many people on board as possible.

The Reefton Revival group aimed to revive and celebrate Reefton’s goldfields character from the 1870s. One of the first big initiatives, straight out of the workshop, was to redesign the proposed new addition of a library to the Buller District Council’s service centre – despite significant pushback from the Council and local residents, the group managed to move forward with their vision for the new building to reflect the distinctive heritage look and wooden architecture of Reefton’s original buildings – despite a more modern build.

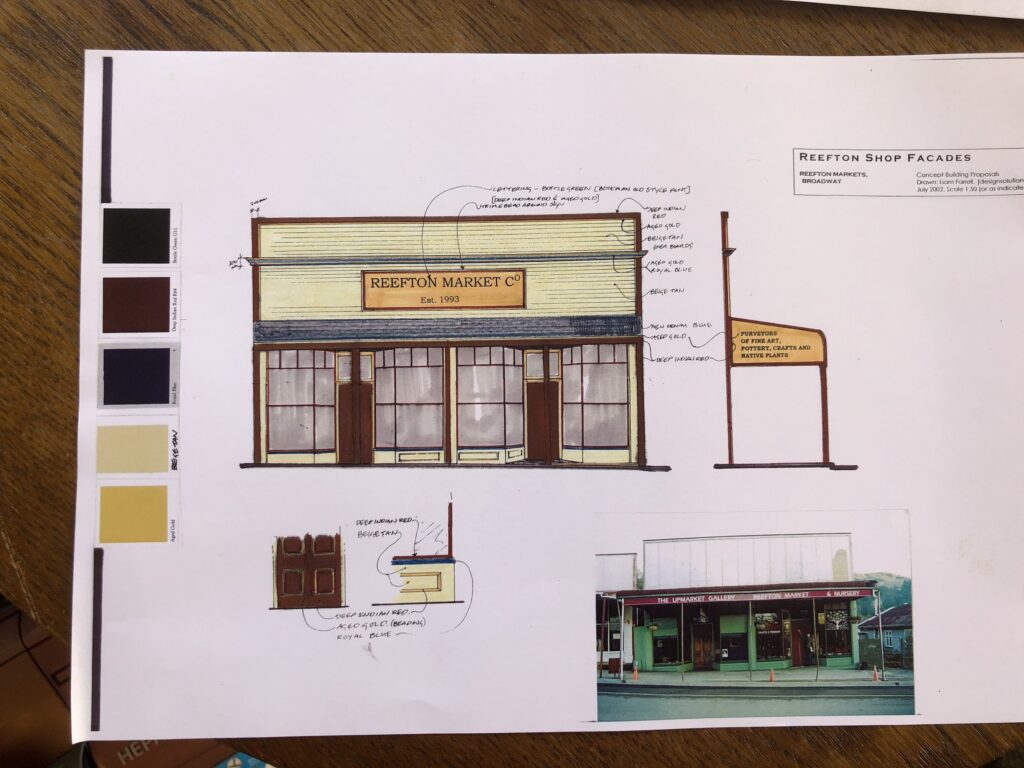

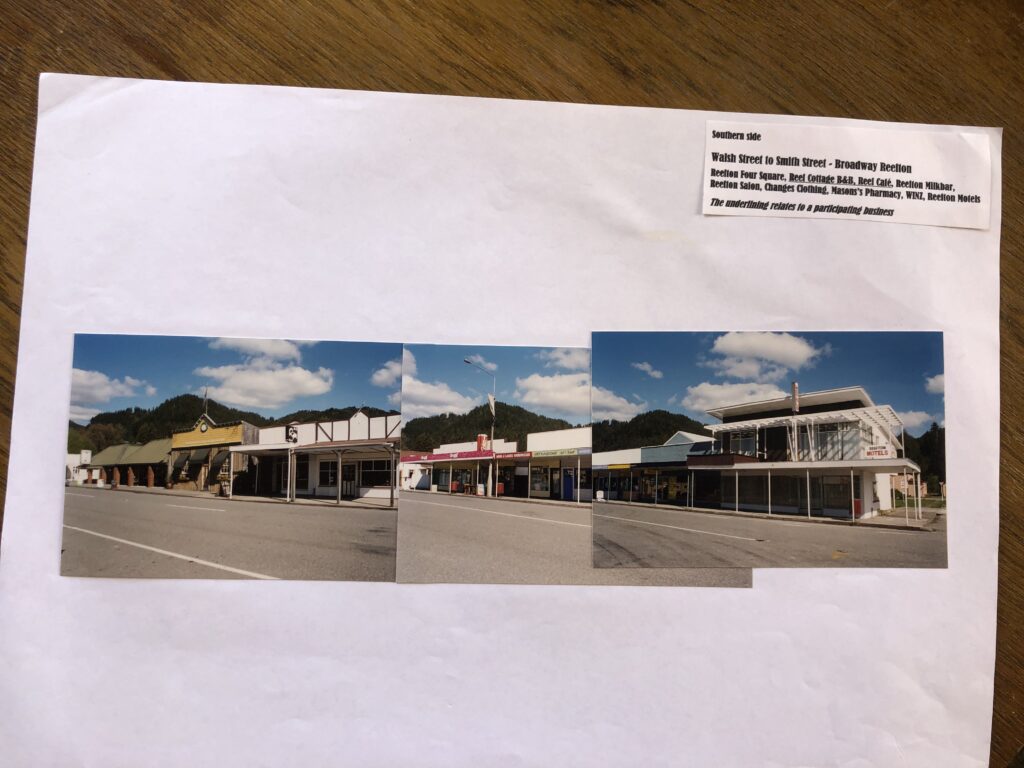

In 2002 the Reefton ‘Shop Front Project’ focused on further bringing back the distinctive character of the town’s main street. “This project was very innovative and transformational for Reefton,” says Paul. Led by the community’s town promotions organisation, the Inangahua Tourism Promotions (ITP) / Reefton Promotions Group, the Shop Front Project group used concept architectural drawings of Reefton’s main street buildings by local landscape architect Liam Farrell to illustrate how they would look refurbished, and together settled on a heritage colour scheme.

The Reefton Tearooms and Bakery are one of the beautifully restored cafés in town.

With the vision in place, the Group applied for the necessary funds from Development West Coast (DWC) to restore several shop fronts on Reefton’s main street. The ITP / Reefton Promotions Group was responsible for managing the loan received from DWC, and to on-loan the funds to individual business owners to restore their facades. “The project was a significant success story for DWC and it was a transformational project for the town,” reflects Paul. “With each phase of the project, we saw more and more buildings restored, as individual homeowners joined in and applied for finance to also fix and paint their buildings.” The cumulative result over the course of a decade created to a substantial lift in the main street’s appearance, which in turn resulted in a great sense of pride in their place for the locals, and in a new surge of visitors who were captivated by the charm of the place.

More than 20 years on, further restorations of Reefton’s building stay true to this colour palette which has resulted in a vibrant and authentic Reefton town centre filled with busy shops, cafes and art galleries. It is this distinctive look and celebration of Reefton’s heritage that really sets the small town apart from others and is not only a source of pride for the locals, but also underpins the town’s plan to secure long-term economic growth and sustainability. This vision has also attracted new entrepreneurs, investors and visitors alike.

Paul Thomas on Upper Broadway where a significant first phase of the Reefton Shop Front Project took place, including the Hale Gallery on the left.

Drawings for the Reefton Market’s transformation into Hale Gallery.

“The investment by DWC into Reefton through the shop front project was an innovative model, a leap of faith at the time for community-led economic development, and it has created immeasurable results that have ensured the town’s long-term sustainability,” Paul says.

Working with diverse groups, ideas and skills

“What has happened with the shop fronts since the early 2000s has been sensational. The face of the town has now changed – now we have a town that we are all very proud of.”

HELEN MCKENZIE

Helen McKenzie grew up in Reefton before moving away in her twenties, and recalls that during her frequent visits back, Reefton was “a busy little town, but things were starting to look a little sad”. Returning home about six years ago, Helen now describes her hometown as being back to its old buzz and attracting new residents with its restored heritage buildings and beautiful surroundings: “People often comment that ‘it’s just like Arrowtown before it got too developed’.”

Helen now manages the local Dawson’s Hotel and reflects that the secret to the town’s resilience lies in its many offerings – unlike other heritage towns, it does not solely rely on tourism. Gold and coal mining remain critically important for local employment, as well as the local dairy industry, the native timber mill and the service sector supporting these industries.

Mountain biking plays a big role in Reefton, for locals and visitors alike.

“It’s all about balance. You need socio-economic stability, but you also need to be mindful of the needs of the community,” notes Helen with a nod to many Reefton residents’ wish to maintain the town’s small size and quiet lifestyle despite its economic growth.

“Where else in the world, after a day of there not being a carpark to be had, can I have a chat in the middle of the main road at 5pm in the afternoon? That’s exactly the kind of town I want to live in.”

JOHN BOUGEN

Paul agrees that it’s the diversity of businesses, skills and ideas that makes the town sustainable, plus the variety of groups and skill sets that are coming together to push forward ideas and projects, citing the current restoration of the community theatre, funded by the Buller District Council as one example. John Bougen, another local resident deeply invested in Reefton’s revival, adds that this fund has also extended to the Reefton Racecourse where the Grandstand and Tearooms are receiving further much needed refurbishment, as well as the restoration of the historically important Railway Station and Oddfellows Hall. Furthermore, another recently received substantial grant will see the Strand Revitalization Project completed, which was initiated 25 years ago and will finally link the town to the Inangahua River on which it was founded.

“It’s a knock-on effect. Once people see that something is working, they want to be part of the success,” says John. “And it’s amazing how you can find the funds you need once you have proven you are actually doing good things for the community.”

Building from strengths

“Authenticity is fuelling Reefton’s future.”

NZ BUSINESS MAGAZINE, DECEMBER 2019

It’s the entrepreneurial spirit of locals and newcomers alike that has been another catalyst in Reefton’s return to vibrancy, agree Helen, Paul and John. One example of a home-made success is the popular Reefton Distilling Co which, founded by another returnee Reeftonian, Patsy Bass, has gained an excellent reputation, and business success, selling their goods both nationally and internationally.

The Reefton Distilling Co is housed in one of Reefton’s original buildings which has been carefully restored to accommodate the working distillery, tasting bar and retail store.

Another is John himself: the self-made businessman turned Buller District Councillor who fell in love with the place and its people when he moved to Reefton five years ago. “People here on the West Coast are so friendly and have such a positive, cheery disposition. Things are possible here, people are open to ideas.”

Humble about his own contributions to Reefton’s recovered economy, John is quick to point out that the community has always been the main driver behind returning Reefton to its old glory:

“The fire has been lit a long time ago -all I have done in the last five years is put a bit more petrol on.”

JOHN BOUGEN

John’s can-do attitude and investment in the restoration and re-purposing of heritage buildings in town have continued on from the Shop Front Project to others, like the repainting of the old mining school, the complete rebuild of the original gaol, along with a number of shops on Broadway, Reefton’s main street. These heritage buildings are now a stunning backdrop to every visitor’s holiday photos and have moreover created local jobs and sparked ideas for new ventures, from the likes of another local who is now building tiny houses at Reefton’s old mill, and Andy and Sarah Parker who have boldly and faithfully restored the old Knox Church.

“Reefton is now thriving and people are committed to keeping this going,” says Paul. John adds that the shared vision is very much to enable and support ideas to keep that momentum going: “The great thing about the West Coast is that you just do it. We have everything here – opportunities are abundant.”

And it’s not just business owners who have been ramping up the pace in Reefton. Local artists and artisans have been busy creating a burgeoning creative and social hub. Their contribution is apparent all over town, including the Friday nights at the Workingmen’s Club which now hosts a vibrant scene. The local galleries have never been busier, attracting more and more visitors. “Reefton has become a real go-to place,” agree John and Paul.

A long-term vision for lasting change

This is also reflected in local government’s attitude towards supporting bigger projects and the continuous building up of skills amongst the community. “There is lots of enthusiasm around the Council table,” says John. “Now is really Reefton’s time.” He adds that while Reefton has a core team of leaders doing a great job at working on the ongoing development of their town, they are also mindful to “leave the door open for other people to come in”.

“There’s always been different key people at different times who have carried things through – everyone brings a different skill to the table.”

Reefton’s Walsh to Smith Street in 2002.

The same area, almost 20 years later: Walsh to Smith Street in 2020.

Paul adds that there has always been real stand-outs among the people who have dedicated their time and energy to their community: “It’s often me who gets interviewed for the papers but without people like Ronnie Buckman for example, we could not have achieved what we have. Ronnie has been pulling cords behind the scenes all these years. Not only was she our first Visitor Centre Manager back in the 90ies and then stepped into promoting our town and cause, she’s been essential to building the relationships between the community and the funding agencies. She’s a local, a real ‘West Coaster’, she’s been our connector for the Revival Project all along.”

All agree that everyone needs to be committed to the long haul – maintaining a flourishing community and a buzzing town is an ongoing project, not one that’s finished after a few years work. Working together as a community is all about finding the right balance between people’s needs and wishes for their town, and the economic realities of keeping everyone in jobs and business. Community and local business development must go hand in hand.

“It’s important to have these constant conversations, is it working, or is it not working? And making adjustments as you go along.”

PAUL THOMAS

Video: The Shirley Village Project

Located around 5km north-east of Christchurch’s city center, Shirley is a vibrant multicultural suburb that’s focused on working collaboratively to make their community even better.

Done with being done to: Meremere’s journey to confident local leadership

Located about halfway between Auckland and Hamilton, just off the State Highway 1, the township of Meremere had struggled to revive its heyday’s spark after the Meremere power plant shut down in 1991 and many residents lost their employment. A sense of feeling forgotten and cut-off created frustration among the residents, and for several years, initiatives by different providers and ‘outside’ organisations had only temporary effects – one sentiment shared by the community was that they felt “done with being done to”.

Growing Collaborative Local leadership

With initial support from the local Council, the Ministry of Social Development, and the Department of Internal Affairs, a group of local residents took matters into their own hands and formed the Meremere Community Development Group in 2011. Thanks some initial grass roots funding like the Community Organisation Grants Scheme (COGS), the group gained momentum and led their first own community projects – these successes built the foundation and vision that then led to the establishment of the Meremere Community Development Committee Inc. in 2013.

Ben Brown, Secretary of the Development Committee, describes the committee as a core group of people that acts as “a sort of super-glue” for the community: “We look after the community-led, the community-based stuff, we help out with people’s community development aspirations.” Establishing this group and voicing the community’s hopes and needs were among the key first steps for the locals to step into their own power to activate change in Meremere.

“We are here for the community-led stuff, for helping to achieve our community’s development aspirations.”

Ben Brown

Read more

“The key thing has been growing a sense of empowerment within the community,” says Mary Wilson, who in her position as Community Advisor for the Department of Internal Affairs, has actively supported the Meremere community on this path.

“With community development, it’s important that supporters also know when to step back and let them forge their own path. Access to funding and resources is only the enabler – the community has to own it and be the driver. For a number of years, Meremere had been ‘done to‘ – they needed time and support to take the lead themselves and do things at their own pace. My role initially was to build their confidence and ability, i.e. the ‘how to’. And look at them now!”

“Funding is only the enabler – the community has to be the driver.”

Mary Wilson, Community Advisor, DIA

Pulling together strength and building a shared vision

Run entirely by a small team of volunteers, the Meremere Community Development Committee is now often found pulling together funding for community events, youth activities and leading projects to add to the town’s infrastructure.

Their first major effort was the design and establishment of a new multi-purpose community hall in 2015, which has been a crown jewel of achievement and a much loved new local asset.

The purpose-built Meremere community hall.

Here, the DIA Community Advisor acted as a broker with the Council to bring the required funding together (Trust Waikato, the NZ Lottery Grants Board and the WEL Energy Trust gave their support) to support the community in developing their vision for their hall – which then drove the project.

“Our hall has been built by locals for locals – people have a lot of respect for it. It’s really an amazing resource for us all – I think any community would love to have a hall this grand,” Ben says of the sense of pride that the new hall has instilled in the community.

Going from being a community that felt left behind to an empowered one that takes matters into their own hands, has been a big learning curve for everyone involved, agree Mary and Sarah Gibb, Community Advisor for Community Waikato. “Now that strong relationships are in place and people know who to reach out to, there is so much more initiative to make things happen. People have learnt that it is ok to ask for help, and that they also have the ability to do things themselves.”

The community hall was transformed into a warehouse during Lockdown – the Development Committee worked together every day to help their community.

This doesn’t mean that there are no more struggles. Both Mary and Sarah point out that making sure everyone feels heard and involved in the community’s future remains a work in progress. “With new people come new ideas and, of course, robust discussions. This is healthy, and all part of the learning and growth,” describes Mary, noting that community development is all about the journey, not the destination.

“It’s about the journey, not the destination.”

Mary Wilson, Community Advisor

Learning by doing – and doing by collaboration

Sarah says that since the Community Development Committee’s establishment, all the agencies involved in supporting the community have welcomed the collaboration and collective achievements in Meremere. “What they achieved during Covid-19 this year was truly exceptional.” In a huge communal effort, the Committee managed to pull together resources from funders, agencies, charitable organisations like the Salvation Army and the regional kai rescue, as well as local businesses and growers, to deliver over 2,000 food and sanitation packs to their community. The fact that Meremere did this for Meremere was also noted with pride by many local residents.

Ben Brown and his fellow committee members did not wait for people to call out for help – they “just went ahead” to ensure their community remained safe and well. Asked about how they quickly pivoted from finding funders to build a skate park (which was made possible thanks to the support of Waikato District Council) to organising truckloads of food and sanitation supplies, Ben shrugs, “It’s a different kettle of fish. We were thrown in at the deep end, and I reckon we swam pretty well.”

Ben Brown and his truck filled with supplies to sort into food parcels for the community.

And this attitude has not changed since the end of Lockdown.

“There are still a lot of people in genuine need for support here,” says Ben. “One of the great things that has come out of our efforts is that we now have a permanent Food Bank in Meremere. It’s run by locals for locals, all volunteers – people here have a lot of respect for it.” Also underway is a community food pantry – again, a network of different organisations was mobilised to pull together resources and workforce to make this happen: the TK Mens Shed built the actual pantry while the produce for it will come from the local community garden.

From immediate response to lasting change

“Going from an emergency response to establishing a permanent social service is possibly the best result for us,” reflects Ben about the Food Bank and Pantry. “There is always a silver lining. Everyone has become much closer through this experience. We now have a much better understanding of our community and who they are, and the whole committee is well known in the community.”

“Meremere will continue to see lots more change, but we will continue our community effort. It’s a wonderful place to live.”

Ben Brown, Secretary, Meremere community development committee

Looking to the future, there’s shared agreement that the “Meremere pride” is clearly returning.

Ben Brown says that the silver lining of Lockdown was definitely that everyone in the community grew a lot closer together. “We are a tight-knit community. We know and help each other.”

“Meremere is in a much better position now, and more and more skilled people are moving to the community. This was evident in the opening of the new library last year: there was a great sense of pride all around – young families, dads pushing prams, the Mayor, everyone was engaged and was so proud,” Mary reflects on the Meremere community’s regained capability to drive their own success. “People are keen to leave a legacy for future generations.”

Ben agrees: “We will continue with our effort here as we are for eternity, until it’s not needed anymore. Meremere will continue to see a lot more change, but those hundred phone calls have been made now – we know we can get help when and where we need it. Meremere is such a tight-knit community. We know each other, and we help each other. It’s a wonderful place to live.”

Predator Free Wellington: Taking a collective leadership approach to build a social movement.

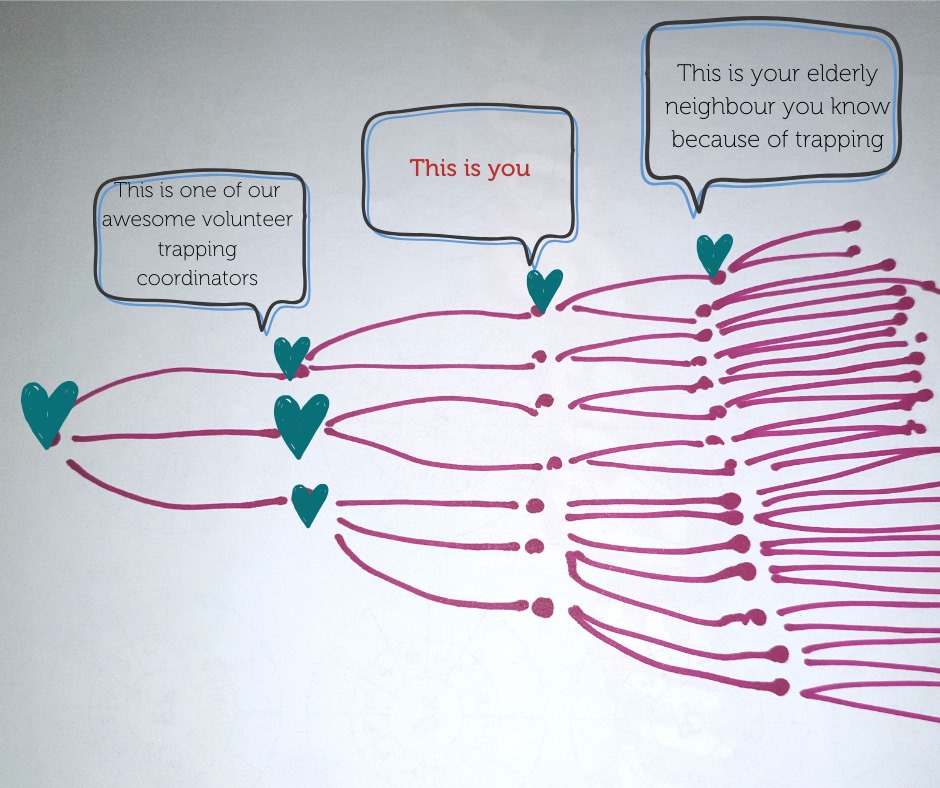

From the get-go, this initiative has been driven by the understanding that the vision of a predator free Aotearoa needs to be strongly rooted in, and driven by local communities. The ever-growing map of participating Predator Free groups, big and small, across the country is testament to the strength and diversity of the Predator Free movement.

James Willcocks, Predator Free Wellington

“People are our biggest challenge in conservation, but they are also our biggest chance. Because if we can have 212,000 pairs of eyes and ears on the case, that’s all the people living in Wellington, that’s the most effective protection network you could ever have. That has been a massive learning for us.”

Across Aotearoa, communities are taking action to enable the aspirational goal of Predator Free 2050. The aim is to completely eliminate the predators most dangerous to our unique biodiversity (rats, stoats, and possums have been identified to be the most damaging of introduced predators). Collaborative efforts are underway at national, regional and local levels to make change happen.

Building on shared local visions

“Taiao – environment at particular places” is one of seven key principles in the national strategy which is enabling ‘bottom up’ innovation and tailored responses. Predator Free Wellington is one of many initiatives underway, their goal to make Wellington the first predator-free capital in the world. They’re moving along at high pace and have nearly completed the first phase of their plan, namely eradicating pests on, and returning native birds to, the Miramar Peninsula. To achieve this, Project Director James Willcocks and his team have built a tight network across the resident community, getting everyone involved in setting up bait stations and traps across the Peninsula.

“We designed this project from the bottom up with the community at the centre. Our vision is for both our communities and our native biodiversity to thrive. You cannot have one without the other.”

Read more

Collaborative Local Leadership

“We really want to create a sense of team and connection for the people. And it’s really worked, neighbours are talking to neighbours about this project, and it’s really driving this huge sense of commitment for the people of Miramar.”

James adds that his team has been absolutely blown away by how engaged the community has been in the project, proving that collective local leadership and the relationships behind it, are the key to success.

“We wanted to kick off a massive social movement. It is not about ‘doing to’ people in that sense – community leaders have stepped up and reached out because they want to do this, and we have then provided them with the expertise, resources and equipment – we’ve given them traps – and they have taken these back into their communities.”

To eradicate the pests, traps and bait stations have to be set up every 50 metres across the grid cast over the area. On Miramar, that is a minimum of 8,000 devices in an area where 20,000 people live:

“Our Engagement Field Officers have gone to knock on every door to talk to people about the project and by doing that, we have received 99% permission to set up traps on private land. This takes a great deal of trust – we cannot take this lightly: you really become part of peoples’ lives when you are visiting them every week. It’s huge social interaction and a huge opportunity for real social outcomes in this space.”

Diversity and inclusivity enable social outcomes

The ability and willingness to look beyond a traditional, westernised conservation model is a key factor in enabling participatory, community-led action. James stresses how much he has learned by working so closely with the diverse neighbourhoods in Wellington:

“Another massive learning for us has been working with marginalised communities or communities that can find themselves isolated, and not going in with a westernised, scientific approach. It is crucial to listen to different communities’ needs and perspectives to really get their buy-in to the project. We all care about the same thing but we will get there in different ways.”

James recalls an inspiring success story with “this fantastic guy who had spent a bit of time on the wrong side of the train tracks” some years ago. This person got involved in the cause because his family could not sleep as they had rats in their hot water cabinet. Having great success with their traps, this family then went on to play an instrumental role in linking James’ team with other neighbours and parts of Miramar who would likely not have felt included in a standardised, top-down approach.

Local action as part of the national vision

“Making Wellington predator free, that’s not my story to tell. It’s the story of the city of Wellington and its people.”

For a successful movement, James agrees that it’s all about thinking outside the box and to go ahead with holistic and broad approaches with the community at the lead, in order to find a way of working together that enables everyone involved. Having a clear goal in mind, and one that is close to home, also supports connection:

“Predator eradication is one part of the rich tapestry of conservation. Setting up a trap is a simple, straightforward action that people can take, and it links them to the broader global goal of preserving and conservation. Tackling big topics like Climate Change can seem impossible for the individual, but if the community can work together and focus on a tangible outcome through direct action, everyone can contribute. We are all part of nature, and everyone has something to contribute.”

Wharekahika: Coming together to protect one another

In Wharekahika (Hicks Bay), the community response to COVID-19 started several weeks before Lockdown already, as an abrupt halt to Chinese log exports led to a surge of unemployment around the East Coast in February. Knowing that whanau would need support with food and other essentials, Ani Pahuru-Huriwai (Trustee of Te Aroha Kanarahi Trust, and Executive Director at Tairawhiti REAP) turned to her networks. She approached philanthropic, iwi and government contacts for funding, Gizzy Kai Rescue for food and her trusted kaimahi to help coordinate the ordering, dispatch and delivery of kai and care packages.

We were able to supply 70 homes with food in the first week of Lockdown, rising to 100 homes in the second week. “

“We were able to supply 70 homes with food in the first week of Lockdown, rising to 100 homes in the second week. This grew to 200 households weekly when our Te Araroa whanau joined us. We had two people ringing homes twice a week to identify needs, and 10 volunteers doing deliveries – in some cases they were driving two hours to reach whanau in really remote places – gravel roads, crossing rivers, stock and subsidence were regular hazards.”

We had two people ringing homes twice a week to identify needs, and 10 volunteers doing deliveries to 200 households every week.”

Hapu and community-led action to minimise risk

But in order to fully protect the community, more, and quite different work was needed during the rahui (lockdown). Despite government messages to restrict travel, tourists were still entering the area prior to Lockdown. In response to this (and following the example of the checkpoints established in Apanui), a hapu roadside checkpoint was set up on State Highway 35 to remove that risk to their community. This was spearheaded by Tina Ngata and Ani, with support from the local hapu Te Whanau a Tuwhakairiora.

Other hapu and communities from Te Araroa to Tolaga went on to establish checkpoints themselves, along with the neighbouring iwi Te Whanau-a-Apanui. The goal was clear: “keep the virus out, and our whakapapa safe”.

“Keep the virus out, and our whakapapa safe.”

Good communication between the checkpoints was essential to achieve this goal, and the checkpoint team made sure to connect daily with others around the Coast, as well as with police and central government. Te Aroha Kanarahi Trust moreover contacted the national Motorhome Association with the request to ask their members and visitors not to travel to the East Cape, as the population was at high risk of contracting the virus. “The Motorhome Association President sent out our email to over Ninety thousand members asking them to respect our request. A popular tourist destination in the area is the East Cape lighthouse, and the landowners closed access to it to help our cause. We were very grateful for such a strong level of support.”

Read more

However the checkpoint team did much more than talking to tourists and closing off the area. “At the checkpoints themselves we were able to pass on information and updates to locals, and even to the authorities who may not have heard it otherwise.” For example, Te Aroha Kanarahi Trust organised a mobile health unit to come out to the top of the Tairawhiti region, which was gratefully received by the community:

“We had 200 people come out to be tested (for COVID-19) – and that was because of all the educating being done at the checkpoints in Wharekahika and Te Araroa.”

ANI PAHURU-HURIWAI

Changes made to last

Things are now slowly returning to a ‘new normal’ on the coast – but some measures would have been most welcome to stay. “During the lock-down we had a doctor here every day, now we are back to limited services. We had four police officers, now we have one.” Many members of the community may have wished for the Level 4 restrictions to continue, as they created such a strong sense of community. People felt grateful for the weekly awhi and manaaki they received during the rahui.”

People felt grateful for the weekly awhi and manaaki they received during the rahui.”

Local police officers joined the checkpoint teams for extra support.

To honour this kaupapa and to move forward, the Wharekahika community are now actively working to increase their resilience. “ A food sovereignty plan is being developed, with different teams responsible for kai moana, mara kai, hunting, food processing and so on. We also realised that having local residents certified as wardens would be a great support for the community, so a Maori warden training programme was initiated and completed, with funding provided by Te Puni Kokiri”.

To thank those who stepped up and tirelessly volunteered their time and resources over the Rahui, the community organised a big Whanau Day and offered koha to the helpers: a recognition that without them, this strong and united response to the crisis would not have been possible. Ani says she is very grateful to the many sponsors, funders, sheep stations and food production companies who provided support.

“Thanks to them, we were able to ensure that even the most isolated whanau in our community were fed and able to keep safe in their bubbles during the most trying of times.”