Embracing Te Tiriti O Waitangi, Fostering Community.

There is a movement towards embracing Mātauranga Māori and understanding Te Tiriti o Waitangi. CLD can embellish this movement in Aotearoa New Zealand. Inspiring Communities' David Hanna, and Pam Armstrong from Whananaki look at how we can deepen our understanding and give examples of what this looks like in practice.

Exciting seismic shifts are happening in New Zealand’s cultural political landscape. The regular use of Te Reo, recognition of Te Ao Māori, and a growing understanding of Te Tiriti o Waitangi demonstrate a movement with the potential to radically re-orientate Aotearoa New Zealand to be a better place for all.

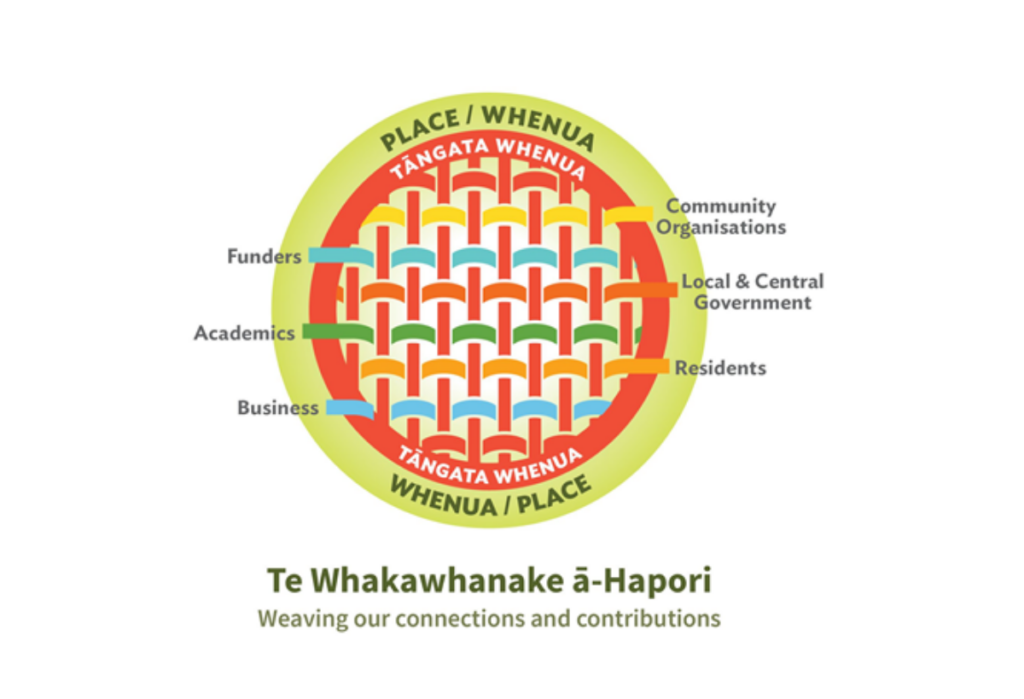

Community-led development (CLD) is one strand that can support this movement achieve effective and lasting change. By fostering connections between diverse groups, we can help shape the aspirations of local communities, grow local leadership and support new relationships that are inclusive and restorative.

CLD views communities as adaptive, complex systems. Communities are living social groupings that are critical in shaping the wellbeing of people and the environment. CLD recognises and affirms the talents and resources that people already have and has a default setting that backs people to contribute to their own wellbeing and development.

Inspiring Communities (IC) is a network of CLD practitioners with a deliberate focus on ‘place’, understanding that transformative change becomes more possible when contributions of all those who have an interest or connection to a place are activated.

This naturally brings into the conversation mana whenua, the people who are of that place, along with the history of what has happened between the many groups connected to place.

We must foster the respect and understanding of all groups, including, where feasible, opposing groups. This isn’t easy. But by hosting conversations between people with diverse backgrounds and views we help foster healthy and resilient communities and facilitate a deeper appreciation of our diversity – as well as what we hold in common.

This deeper engagement and connection can lead to subtle shifts that open the possibility for new thinking and ideas to emerge that hadn’t existed prior. Resiliency is formed through the mix of connectedness and diversity.

Globally there is growing interest in locally led change. The challenges of inequity, climate change, racism and environmental restoration are renewing interest in the key role local citizens hold. This is reinvigorating the old concept of the Commons – those resources or parts of nature that one cannot own. These trends reflect emerging fields in science that flow across many disciplines and emphasise a more inter-connected, relational and natural world view. This ‘new’ thinking within ‘western’ science circles has similarities with indigenous knowledge systems that have been passed between generations and survived the challenges of colonialism.

This ‘freeing’ up of knowledge from narrowly defined Eurocentric world views enables indigenous knowledge like Mātauranga Māori to claim its rightful place in helping shape more just and sustainable ways of living.

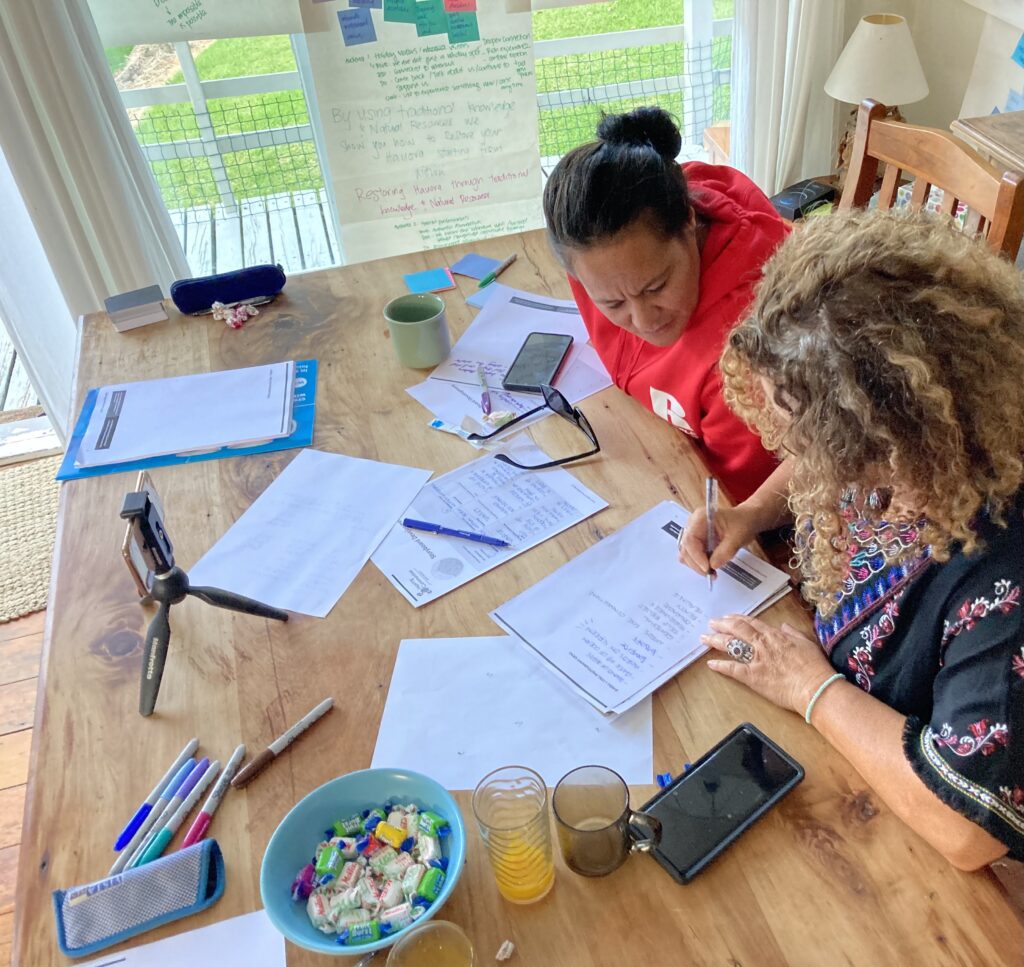

Whananaki on the east coast of Northland is an example of this approach in action. Locals have set aside many years of the ‘us and them’ mindset to bring the best of both worlds together for the betterment of their place. The community is noticing that shift and say their place is much richer for it.

A number of initiatives have flourished; from development of the marae, to planning a local community hub, a youth-led social enterprise project working to produce natural and Māori medicinal plant-based balm and bath bomb products, to the development of a large-scale native nursery. An indigenous lens has been applied to pest and weed eradication. Previously, contractors from outside the district did the work. Now, the contractors key role is to teach locals the skills so that the community develops self-reliance practices. While it will take longer, the expertise will remain in place with the community.

Whananaki local Pam Armstrong says the adoption of community-led development approaches sitting alongside Mātauranga Māori has firmly shaped their vision for a culturally connected caring community. You can read her full account here.

This bringing together of different world views is not a new concept for Aotearoa. In 1840, Te Tiriti o Waitangi brought together two markedly different world views into one document – albeit with numerous versions. Mātauranga Māori met rational European science and law.

The shared intent of both parties entering into the agreement was a desire for an agreed framework to guide the on-going boundaries and relationship between all parties. Unfortunately, a great opportunity was squandered by the colonial mentality of European controlled governments.

By 1840, Māori had already demonstrated their adaptive capacity to integrate European technology into their tikanga. Imagine what could have formed if Pākehā demonstrated the same openness to integrating Te Ao Māori at this historical juncture?

To arrive at an agreement, Māori debated and interpreted Te Tiriti’s value and meaning from their indigenous body of knowledge and the significant evidence they had accumulated on the relatively new arrivals. In contrast the overarching British approach was informed by over three hundred years of conquering and colonising and the legal and political frameworks that had been established to maintain their global empire.

The resulting power imbalance and the brutal suppression of rangatiratanga (chieftainship) meant the opportunity to jointly shape the interpretation and application of Te Tiriti was radically diminished.

From a Mātauranga Māori perspective a ‘deal’ between different groups requires ongoing work from everyone that is party to it for it to maintain value and aliveness. Clearly for the majority of New Zealand’s Pākehā history this didn’t happen. The current Te Tiriti movement is addressing this fact, as one party to the agreement plays catch up. Community-led development and its related tools provide helpful resources to address this neglect and support bringing life to the vision it established.

And what of the role for government and its institutions? A current trap is their failure to appreciate how their way of working reflects dominant Eurocentric assumptions. Communities as living systems are not well served by either market-driven or state-driven responses. Non-financial transactions are invisible and not considered in policy solutions.

Policy analysis has become a craft that minimises the deep wisdom and insights of people experiencing the issue and their capacity as actors in driving solutions. Open participatory conversations in communities are different to government hosted consultations.

If government maintains the same operating system, then it risks the outcomes being simply a new Treaty veneer – lacking the necessary deep systemic change required to do justice to our foundation agreement. Too many command and control or paternalistic approaches erode the connectedness between citizens and the Crown.

Te Tiriti is not a problem to be fixed or conversely the answer to all our problems but must be valued as a resource to guide on-going innovation and renewal.

Crown leadership, exercised correctly, is essential to honouring Te Tiriti. CLD necessarily extends the range of leadership styles. It values community leaders as hosts and brokers of relationships. This contrasts with our common expectation for leaders to have all the answers. CLD places an emphasis on open processes, sharing of information and hosting conversations. On-going learning and adaptive approaches are encouraged as opposed to rigidly sticking to set plans and timeframes.

While not a speedy process, it has potential to deliver more lasting solutions (which ends up being the quickest route to the desired destination). Inspiring Communities practitioners know well the wisdom of moving slowly to go far!

Rather than placing the sole responsibility on a narrowly defined Government to fix the problem, local communities’ step into their leadership and become part of on-going solution seeking and sense-making processes. What evolves may look different in each place with unique local context and history shaping different priorities.

CLD can embellish the current Te Tiriti o Waitangi movement. It can help reenergise citizens and is able to hold the diversity and contradictions that exist in our complex world. This shifts Te Tiriti from being seen by most Pākehā as a ‘Māori’ issue, to it being a special and unique resource for all citizens to pave new approaches. In doing so, we can strengthen the vitality of local communities, strengthen democracy, foster connections between diverse groups, develop leadership and affirm the strengths and taonga already within our places.

Please read the full length article from David here, alongside Pam’s article, The Strength of Whanananki.