Tensions, Learning and Adaptation

There will always be times when uncomfortable tensions arise. Leaders need the courage to challenge unacceptable behaviour and acknowledge their own weaknesses too.

Leaders can help create and model a non-defensive climate of learning, reflection and inquiry where people can give and receive feedback and find a way forward. Effective leaders take time to reflect on their own thoughts, assumptions, feelings and behaviours. This allows them to understand the part they can play, and what is beyond their control or is not a priority to try to change right now.

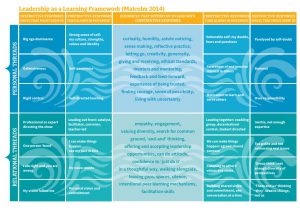

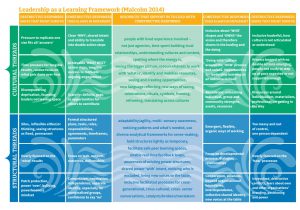

The Leadership as Learning Framework describes four interwoven dimensions of change: personal, relational, structural and cultural. These are also identified in our Quadrants of Change framework as important areas to pay attention to if we want to impact and sustain transformation in communities.

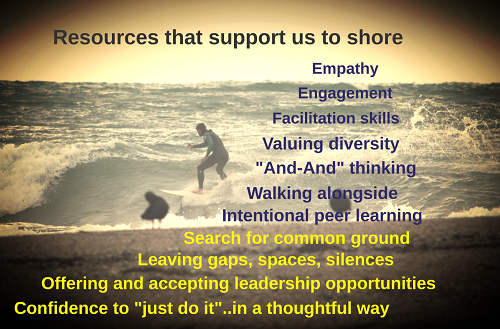

Leadership is a bit like riding a surfboard on an always moving sea. Sometimes the tides ebb and flow gently and simple habits like being open to feedback help us re-balance. We can go from vulnerable “I don’t know” moments back to our strong selves with relative ease. Other times, bigger waves dump us into stormier waters. Rip-currents might even push us towards the edge of chaos. We come up against the darker sides, the challenges, the not so helpful behaviours, attitudes, and ways of thinking and acting. To escape from drowning in rip-currents we have to swim in not so obvious directions, finding our inner strengths and other resources around us, to come up with responses that we may never have thought of before. While it’s not a comfortable place to be in, the collision of these lighter and darker sides actually provides a creative space for innovation, learning and dynamic change.

The centre column of the Leadership as Learning framework reminds us of some of the resources we can draw on to lead us through the normal tides, waves and rip-currents of community leadership. The inner two columns on either side of the centre show some of the constructive leadership behaviours, attitudes and actions we can apply in the normal movements of the regular tides. These might look like polar opposites, but each has their time, place and use.

The outer two columns identify more destructive responses that can happen if we take positive leadership responses to any extreme. For example, the dark side of being strong can be a big, controlling ego; the dark side of vulnerable can be paralysing self-doubt. The framework encourages us to not get stuck in any one place but to see this as a sea that needs to keep moving to stay alive, learning, growing and innovating. As leaders, that means being aware and constantly adapting to what’s needed for each new wave or situation.

Let’s take a brief look at each of these four layers, helping you explore this framework with some reflective questions about what you can do to grow:

- your own leadership

- the leadership of others around you

- the leadership of organisations you work in

- the leadership of communities you live and work in

Each section includes a fictional story to illustrate the ideas offered. You can also read some of our Inspiring stories that highlight the many amazing things that communities are already doing.

Here we try to unpack some of the back story of the leadership challenges and responses that often sit behind such fantastic results. We hope these stories and ideas will support you to work with the complexities and messiness of CLD work and encourage you to hang in there to make things happen.

The Personal Thread: Leading Ourselves

Take a moment to look at the personal threads identified in the framework. What resonates with you?

Common fears that hold people back from being active citizens or taking on leadership roles include personal fears of change, of not knowing what to do, of failure and loss of face. The challenge is to not stay stuck in these fears. We can enhance our leadership by asking reflective questions to identity our fears or sticking points. This can help to open ourselves up to the possibilities for changing the situation.

How could you think, engage or act differently in your personal practice to ensure that you:

- keep the good aspects of your humble self-doubt and feel confident that you will find your strengths as you step out and take action, despite your fears of the unknown? What if you turned your fears into questions you wanted to explore as a curious, inquiring learner? What do you most need to receive or give, offer or accept? What do you need to sustain you on the journey?

- maintain your self-confidence and an awareness of others who may feel reluctant to help when you are so competently handling everything? Have you got the courage to let go of some tasks and ask others to help, even if they might do things differently to you? Even if things might not happen at all? Are you being too responsible – or maybe not clear enough about intentionally sharing power and control?

- have regular time for reflection about recent events, e.g. what you are grateful for that has happened today; what your intentions were for the day; how you wanted to be; what you notice about your behaviours, thoughts, questions, feelings today; what your intentions are for tomorrow. How can you choose to respond to enable your own and others’ leadership? Are you being too hard or too easy on yourself? Remember the power of small action to produce big outcomes.

Peter was helping get a community garden underway. It was exciting at first just doing it. He was confident helping build planter boxes, planting, weeding and tending the vegetables. But it soon became clear the more complex part was building good relationships between the people involved and with others who wanted to join in.

Peter and two mates from the garden went off to talk to another local community garden group to share experiences and pick their brains. They decided to visit each other’s gardens on alternate months for practical working bee help and some chats over a cuppa about what each garden group was learning about running a great garden. They now feel more confident to work through organisational issues – not just the veggie growing – because they are not alone. They get new ideas and insights from each other and in between times share cool stuff they find on the web and Facebook.

Three key ingredients that support our leadership learning

CLD leadership work focuses on creating an environment where everyone is encouraged to contribute their diverse strengths towards the leading, doing, thinking and learning. At least three key ingredients can help support anyone’s leadership learning.

- exposure to new ideas that stretch our thinking beyond the familiar (e.g. from something we read or hear or a workshop we go to). Typically this provides 10% of our learning

- opportunities to try out new practices (e.g. behaviours, skills, tools, approaches in practical situations that stretch us beyond our established habits). This provides 70% of our learning

- safe, high trust learning spaces to reflect with our peers (e.g. about what we are all learning from each situation and where we can still grow further). This provides 20% of our learning

Food for thought…

What’s missing or needs rebalancing around these three factors for you or your community group?

What simple steps could you take to reach out and create opportunities for the missing ingredients that you or your group need(s)?

The relational thread: leading with and alongside others

Take a moment to look at the relational threads identified in the framework. What resonates for you?

CLD doesn’t happen if it’s just one person with a vision being the expert and everyone else following. We do need people with bold visions who often create or promote change. But the sustainability of community-led change comes from building a shared vision over time. It happens one conversation or action at a time, with many voices and perspectives, using many different ways of making things happen. CLD leadership challenges us to find ways to be truly inclusive, and grow the leadership of the many, not just the few. Sometimes we’re overloaded, drop some balls and find we have left a useful gap for others to step into. Whether by accident or intentionally, leaders need to keep moving between leading out front, walking alongside or stepping right back to leave space for others to lead and meaningfully contribute.

What could you do to strengthen respectful, shared leadership in the CLD spaces you are working in

- to truly honour and grow the diverse strengths of the community you work in? How do you check you are really hearing what others are saying, what they are meaning, what they are offering? How do you offer encouragement for others to step into the unknown and see their potential?

- to ensure you don’t lose your own voice, while working hard to listen to, empathise with, understand and include others’ views? When do you stand up for some really important principle or purpose and when do you hold back because it’s more about your own ego or need for control?

- to ensure you don’t get locked into them and us thinking? How truly open are you or your group to other ways of thinking?

- to keep noticing where you need to lead from at different times and places – out front, walking alongside, from behind, or stepping right out?

A few years ago Peta started community pot luck dinners in her neighbourhood. After a while, they were taking place four times a year, and attracting up to 100 people each time. Peta was quietly proud of the way she had slowly stepped back from being the driver for getting these dinners started. She involved others in looking after different things like publicity, the kitchen and activities for the children. She was consciously trying not to be a one woman band by taking responsibility for everything. Those she was actively encouraging were now stepping up to keep these dinners going.

Then one night there was a tense discussion in the kitchen. A large group of students who had recently moved into the neighbourhood turned up at the dinner without bringing any contribution and then ate before other families, meaning some missed out on getting enough to eat. Some people felt strongly that they needed to say something to the students. Others felt they should just be inclusive and accepting of everyone as they are. Peta listened for a while, then one of the group turned to her and asked what she thought.

Peta wanted to shift the conversation, so she asked a powerful question: “What could we do to make sure everyone in this community is welcome here, whether or not they can bring food, AND that whatever is brought is shared?” The group soon agreed that they needed to communicate these values in what they said at each dinner when blessing the food and welcoming people. That night they made the students welcome, encouraged them to come again and shared the story of how the dinners got started.

Peta reflected on how she had needed to take a different leadership role this time. It would have been tempting to just express her opinion. Instead, by asking a powerful question, she was making her voice heard, and helping the group learn to work through issues and get beyond them and us thinking. At the next dinner, the students returned and brought pizzas without anyone having to ask them to contribute.

The cultural thread: how we work with each unique community context

Take a moment to look at the cultural threads identified in the framework. What resonates for you?

It’s tempting to think we could find out what works and do exactly the same thing across lots of communities. But each community has its own unique context, history, culture, stories, identity, complexities and ways of getting things done.

We can’t apply solutions that have worked elsewhere and expect them to work. We need to build home-grown strategies from local relationships that bring knowledge of the strengths and complexities of each local context. We also need to keep sharing lessons and stories from one community to another.

It’s often the culture around how people have worked together that we can learn most from, not just what they have achieved. How did they identify where the energy was? What were the things that failed and why didn’t they succeed? How did they stay resourceful to keep everyone on the waka through the ups and downs of their journey?

What needs to shift to break unhelpful patterns in the culture of your community initiative?

- How involved are those with the lived experience (e.g. local residents or people affected by the issues or change you are working on)? Are things mainly led by agencies and professionals? What actions could encourage more of a ‘doing with’ than a ‘doing for’ or ‘doing to’ culture? Who needs to be more engaged with the decision-making? How could that happen?

- To what extent is “the way we do things around here” named, known or discussed? What are the positive and negative aspects of the existing community culture? Has the group ever had a discussion about core values and behaviours/attitudes they would like to model as a way of people working together? How are those expectations communicated to others? How do people deal with behaviour that is inappropriate or unsafe?

- Do people understand the shared purpose, the processes, the next steps? Is there a strong culture of collaborative inquiry to shape these so they are really grounded in the community’s ideas and owned by a wide and diverse group of people?

- Is there a healthy tension between strengths-based thinking and using gaps//failures as opportunities to find new community assets and for new people to contribute? Are founding leaders leaving space for others?

- How do you make the most of uncertainty, messiness, diversity, tensions? How could you reframe these uncomfortable spaces as key opportunities or energy sources for learning, innovation, new approaches and new possibilities?

Sione, a youth worker at a local church, engaged with some young people in the neighbourhood who had dropped out of school. At first, Sione just hung out with them. Over time he earned their trust and came to understand their way of seeing and doing things and the young people started to share their aspirations. Together they decided it would be great to have a place to call their own, and Sione agreed to ask the church if their vacant house could be used, now the church no longer employed an assistant minister.

The church council agreed it was a great idea, and had potential to be a Youth Hub for the city, but they didn’t have the capacity to manage it. They suggested giving the oversight of running the house to a governance group made up of key church, education and social service agencies in the town who had a lot of professional experience in working with youth in the city. They felt this would provide an excellent focal point for inter-agency collaboration around youth development, as well as property management.

Sione went back to the young people to share the good news that they had got the house, but he was surprised by their responses. What’s this Youth Hub idea? That wasn’t our idea! Why would we trust those people on their committee – some of them kicked us out of school! They wouldn’t listen to our ideas. Why don’t they trust us to look after it all?

Sione believed there was some common ground between the ideas of the young people and the church council, but he had a big job ahead to create a bridge between such different ways of doing things. So, he asked the young people: “If you trusted the church or any committee to really listen to you, what would you tell them about your vision for this house? What would you see happening there? How would people treat each other? What would be needed to make this a cool, safe and creative space you really wanted to be involved in?”

Sione and the young people invited the church council to share fish and chips with them the next week. It was a bit tense at the beginning, but as they discussed Sione’s questions, and listened to each other, they started to see how they could make it work. Their most important decision was that the young people and the church council would work alongside each other to decide on the next steps together.

The structural threads: working with sound and flexible organisational processes

Take a moment to look at the structural threads identified in the framework. What resonates for you?

CLD takes us out of our silos and our assumptions about how to do things effectively. CLD often invites us into different thinking spaces or experimental actions that go across and beyond traditional role boundaries. For example, it might mean bringing together governance, management and staff for a focused discussion, or it could mean that different sector organisations and people of different status are brought together who wouldn’t usually meet.

There are times when writing down decisions to form plans, job descriptions, agreements, diagrams and reports really helps make clear what needs to be done, by who, how, and later, the results that were achieved. It’s great to have a clear action plan that everyone can agree to and get on with.

There are also plenty of times when discussions have no immediately visible outcome. It can feel messy, complex and slow for new thinking or actions to emerge. Investment in relationships, trust and understanding is needed before any concrete plans or action can emerge. Once plans, systems or structures are put in place, the challenge is to make sure they aren’t too fixed. We can’t fully anticipate the ripple effects of all the actions we try out in the CLD space. Some will fly beyond our expectations, others won’t get lift off.

We have to stay flexible, carefully listening and noticing what is emerging and planning next steps as we go. We also need to be open to adapting any structures, plans and processes we put in place. That’s because CLD is complex, and takes us into unknown, unfamiliar territory where answers emerge out of our korero (conversations), our whakawhanaungatanga (relationship building), our mahi (trying things out) and our ongoing ako (learning with each other).

What structures, systems, processes or plans are useful in your community context:

- to identify what the group has in common in terms of shared identity, vision, values, culture and what can be left diverse, flexible and emergent in terms of perspectives, pathways and plans towards the vision?

- to support regular individual and collective reflective practice to keep learning from what you are doing, the patterns you are noticing and to make sense of the best way forward?

- to manage power dynamics and shift unhelpful patterns of behaviour or attitudes that might be limiting energy and discouraging shared leadership?

- to avoid overly fixed roles, plans, boundaries and structures to enable flexible exchange of information, assets and energy across all who want to engage in the kaupapa?

Jane, recently retired, moved to a small rural town to be closer to her mokopuna. Soon after she arrived, NZ Post decided to withdraw the town’s only Postshop and Kiwibank services. This not only cut essential services but threatened the viability of the only local store. Jane went along to a community meeting attended by many locals, and found herself offering to help on the committee that was going to lobby NZ Post to keep the services and at the same time look at alternative ways to sustain the local store.

At the first committee meeting, Jane offered to use her professional marketing skills and experience from her previous Wellington work to draw up a campaign plan. She went and talked with the local store, school, church, kohanga reo and kaumatua about their networks and potential contribution to the campaign. When she presented the plan at the next meeting, there was a mixture of gratitude and scepticism around the table. “All these fancy words look great on paper but I’m not sure it will change anything. Wellington has never listened to us, so we’ll have to find our own solutions.” Jane was surprised at how powerless many felt and hoped her skills could help.

Over the coming weeks, it became very clear to Jane that her initial plan to assign different tasks and roles to different people on the committee was not going to work like it did in her previous Wellington management role. Things happened in a much more organic way in this town, and it was still early days for her in getting to know people, let alone in getting people to trust her. So she held her plan lightly, and shifted to the “one conversation at a time” strategy instead. She spent time getting to know the key local community people who would make or break this campaign, and gently dropped into the conversation possible actions that they or she might take. They shared tea, scones, beer, laughs, stories and outrageous possibilities, till they landed on agreed actions. There were heaps of skills and resourceful people here. They were just different from the ones in Jane’s previous life.

The committee met weekly to keep momentum going. Jane’s plan was still there in the background, but mostly action plans emerged from weekly committee discussions, depending on how NZ Post were responding and who else was coming on board. They managed to get a temporary delay from NZ Post for 6 months and refocused their energy on ways to keep the local store viable. Their vision was a new café for locals and visitors at the local store and they expected it would thrive when a new cycle trail opened a year later. Jane reflected on how much she was enjoying about listening, learning and being adaptable in this new phase of her life.